Adoption creates a split between a person’s biology and her biography. As an adoptee grows, she may wonder why she was placed. She may fantasize about the life she’s not having. She may wonder about her medical background, about her biological siblings and her extended family members. She may wonder where she got this talent or that trait. She may worry that she was unlovable. She may wonder about meeting these mysterious but very familiar people.

Openness is an effective way to help heal that split—whether through knowing her birth family and being able to ask these questions, or through your openness to her questions, to admitting that you might never know the answers, and helping your child process the grief that that brings. Because the question isn’t whether or not your kids will have complex feelings about their adoption, whether or not they’ll have grief and “otherness” to work through; the question is, will they feel comfortable sharing these feelings with you?

That’s the premise of the book I co-authored with my daughter’s birth mother, The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption: Helping Your Child Grow Up Whole. So, how open can we as parents be? How open can we be to our child’s wonderings? Does it hurt us when they talk or fantasize about their birth parents, or are we able to know that that’s not really about us? How open can we be to our child’s efforts to discover and build his identity? Openness is not always the easy path, but it is very much the worthwhile path. How do we get there?

Expanding the Concept of Openness

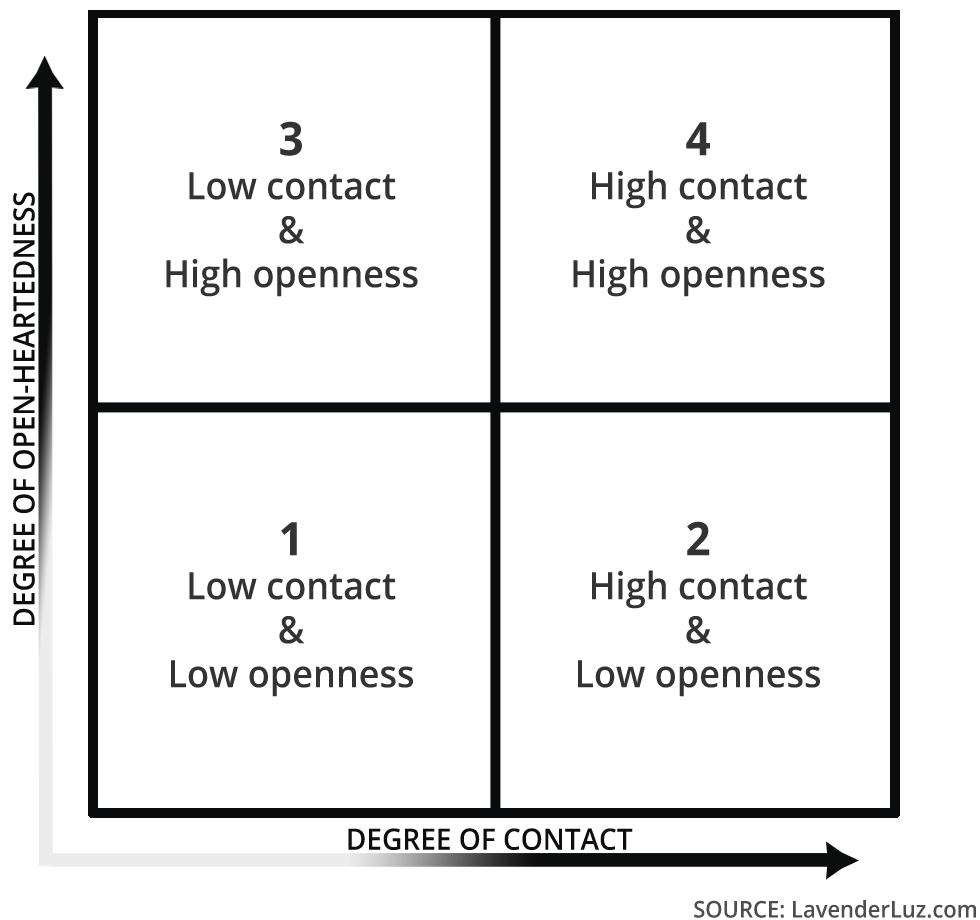

When people think of open adoption, they often think of openness along a spectrum, from no birth parent contact to some contact to full, in-person contact. I submit to you that openness is really more about a mindset or a “heartset” that we employ when we parent a child through adoption. Let’s add another dimension to that concept of openness, and pop that line into a grid. Here, we have the open adoption grid.

Along with the line for contact, we also have an axis for openness. You can have neither, you can have one without the other, or you can have both. Contact, whether that’s simply an exchange of identifying information or full integration among families, is what happens among the adults. Openness, on the other hand, is what happens within each parent, and between the parent and the child. We may have only partial control over contact, but the good news is we have full control over openness.

Let’s take a brief tour of this grid. Box 1 is the traditional closed adoption box. Not only is there very little contact or identifying information available to the child because of closed records, but there is low openness about adoption in the family. Why? Maybe the parents have unresolved grief left over from their infertility struggles. Maybe they were counseled to act as if their child were born to them. Maybe they were told that their baby comes to them as a blank slate.

This box, shrouded by shame and secrecy, may be the most crippling for a child to grow up in, the least conducive to integrating her identity from both her sets of parents.

In Box 2, we do have contact with the birth family, maybe through exchanges of photos, e-mails, or even meetings. Parents here may say things like, “Well, we follow our open adoption agreement,” or, “We’re willing to send monthly updates and pictures.” What’s lacking in Box 2 is the spirit of open adoption.

Adoptive parents here may not have processed their own emotions. They may harbor feelings of envy, of fear, or even superiority about their child’s birth family. They may enjoy having all the power that they hold in this relationship, rather than inviting the birth parents to co-create an open adoption relationship together. And the children in this box pick up on the emotional gap between their clan of biology and their clan of biography.

Box 3 is where we find many families by foster or international adoption, cases in which contact is either not possible or not wise. Despite low contact, for reasons that may be outside the control of the adoptive parents, there is high openness. The parents in Box 3 deal with their own emotions about their family-building story and parent with an open heart. They’ve neutralized the word “real” and they feel real from the inside. They’re also able to acknowledge that their child’s birth parents are equally real, without that thought taking away anything from them.

Parents here are able to open their hearts to their child as she processes her adoption story and integrates her identity over the years.

Lastly, Box 4 is where birth family is considered extended family, both in terms of contact and in openness. The relationship may be no different than one we have with a beloved uncle or sister-in-law or grandmother—or even a relative who’s not so beloved, because as we know, sometimes we’re connected by family to people we’re not crazy about. Nevertheless, we make it work because they’re family.

The relationships here are child-centered and inclusive. The child is claimed by and able to claim both her clans, helping her to integrate all her pieces as she grows through her toddler and her school years, through her tweens and teens, and into adulthood. She is not pulled to choose or rank one family over the other, and she’s therefore less split. She’s free to pursue wholeness in her identity.

Please note that Box 4 is not “better” than Box 3. Adoptive parents have full control over the elevation on this grid, but only partial control over the amount of contact. So how do we embrace openness and get to quadrants 3 and 4?

Excavate—and Disarm—Your Triggers

A while back, a national morning show featured an adult adoptee who reunited with her birth mom after 30 years. After it aired, a woman started a thread on an adoption bulletin board because she was incensed about two things. She was upset that the birth mom was called “Mom” by the adoptee and by the narrator, and that the adoptive parents weren’t mentioned in the segment. Other adoptive moms on the forum chimed in with their hurt, too.

Big emotions like these are signals that we have a trigger, a place inside that hurts. Clearly, this was a trigger for the women on this thread. They felt negated, they felt neglected, they felt invisible; demoted from their hard-won position as Mom. They wanted their place in the hierarchy to be recognized and honored.

It’s understandable that they felt that way. We all have some emotions that are icky and unflattering. But those below-the-surface emotions can create problems for us and for those around us when they inform our above-the-surface actions and words. This often happens without our even knowing that it’s happening.

Some common triggers are:

- The word “real” — “Real” is a word that we in adoption are quite familiar with. It’s our nemesis. It sets up a winner versus a loser; the legitimate versus the negated, and our thoughts automatically go into duality. Am I the real mom, or is she? It makes us discuss nature and nurture as a debate, nature vs. nurture. Open yourselves to the idea that both have value. That your child’s heart can be so open and so big that he can love all his parts. We adults must show that it can be done by also loving all his parts.

- Shame — In adoption, there has long been too much shame. We have the shame and stigma of infertility, of not being good enough to swim in the gene pool. We have the shame and stigma of getting caught in an unplanned pregnancy, and we have words like “bastard” that remind us that there has been a stigma and shame for people who were born to unmarried parents or who joined their families through adoption. Adoption has been steeped in shame, but openness is the antidote to shame, not only for your child, but for you as well.

- Claiming — Claiming your role as a real parent is necessary, and so valuable, but it can be destructive to your child if it takes on a sense of exclusive ownership. Say a birth mother makes a comment during a visit, or about a photo you post to social media, saying, “My son is so cute.” If this is a trigger, you could have a conversation with her and say, “This is how I prefer you talk about our son or my son.” Or you could look at it and say, “Hmmm. Why is that bothering me? What can I do to make it not bother me?” Because he is her son—she gave birth to him. And he is your son, too. You can move from the “either/or” to the “both/and.”

If you dig deeply enough to find your hidden triggers, I guarantee you’ll be able to resolve them, because here’s the secret. Once you dig out a trigger, it loses most of its power. That’s the power of openness and light. And the more triggerless you can be regarding adoption, the more likely your children will share their feelings and their healing journey with you.

Embrace a “Both/And” Heartset

My aim for my son and my daughter is to never feel split, to never feel as if they need to choose or divide their loyalties between their birth parents and my husband and me.

I received validation that I was achieving my goal on the morning of my son’s ninth birthday. As I hugged him good morning, I playfully exclaimed, “You’re my favorite son!” In response, he hugged me back, and said, “You’re my fav— you’re one of my favorite mommies.” Now, there are two ways I could have interpreted his proclamation. Either that I am in competition with his birth mom and I’m not out-and-out winning, or that my son’s heart is so big that he can hold us both in it.

The former notion would cause me pain and jealousy, the latter would fill me with joy and pride. Which one do you think I chose?

LORI HOLDEN writes from Denver at LavenderLuz.com. Her book, The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption: Helping Your Child Grow Up Whole, written with her daughter’s birth mom, is available through Amazon or your favorite online bookseller. Holden is mom to teenagers Tessa and Reed.

LORI HOLDEN writes from Denver at LavenderLuz.com. Her book, The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption: Helping Your Child Grow Up Whole, written with her daughter’s birth mom, is available through Amazon or your favorite online bookseller. Holden is mom to teenagers Tessa and Reed.