We all imagine alternative scenarios for our lives. What if I had chosen a different career or college, or a different town to settle in? What if I had bought Apple stock 20 years ago? What if I had married my first love? These musings about alternative paths are generally fleeting, lest we become steeped in regret. But for adoptees, these “what if” fantasies can be particularly tantalizing, because the possibility of a proxy life seems less ephemeral. We actually had a second family, a genetic heritage, and perhaps another country and culture of birth, from which we were separated. I think of these reveries as “sliding doors,” a reference to a 1998 movie that illuminated the flawed projections and presumptions of these fantasies.

Sliding Doors laid out two different, parallel paths of a woman’s life, depending on whether she made or missed a subway as its doors slid closed. Each version of her life unfolds with surprising twists and turns depending on this one random event. In the scenario when she makes the train, she is able to catch her boyfriend cheating on her, leave him, and find true love. It seems to be the better path. But then, soon after, she dies after being hit by a train. In the second scenario, she is oblivious to her boyfriend’s ongoing betrayal and stays with him. But when she is hospitalized after the tragedy of losing a baby, she finds that same true love. Only this time it may last.

The fact that adoptees are cleaved from their genetic relatives and sometimes further separated from culture and country is fertile ground for imagined alternative scenarios. As a child, the daydreams can be filled with fantasy. Am I secretly a princess or a prince? Is my mother or father a famous actor? As we get older, the questions become more sophisticated. Would my life have been more congruent if I’d grown up in my country of birth? My father is an alcoholic. Would my childhood have been less chaotic if I’d grown up with my birth parents? This fantasy life was a haven for me when I was angry or hurt as a child. I would conjure up my “real” parents who shared my gap-toothed smile and passion for reading.

The problem is that alternative versions of our lives are no more real than Aladdin’s genie. There is no way to know what would have happened had the twists and turns of fate spun differently. Maybe you would have grown up feeling more comfortable in your skin, but maybe you would have died, as a baby, from a virus. While your adoptive father was an alcoholic, your birth father may have been violent or abusive. Maybe one of your birth parents is, indeed, a princess or an actor. But as in Sliding Doors, if fate had dealt you a different hand, it might have had all kinds of colors, beautiful or tragic. The imagined alternative versions are not missing or lost; they simply do not exist. There are losses inherent in adoption, but mourning a loss that never was only adds to the burden.

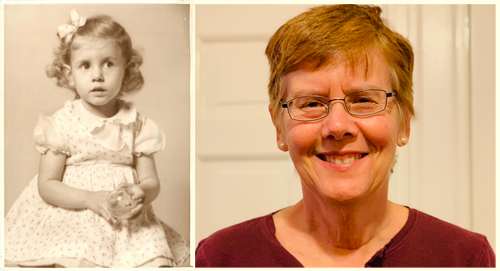

Author Brenda Cotter, as a toddler and now.

In my 20s I found my birth mother and other genetic relatives. What was most interesting and satisfying was seeing all the genetic touchstones that others take for granted. Some of them did, in fact, share my front tooth gap and I felt a real connection, born of our overlapping DNA. But my immediate epiphany was that there were no options for alternative pasts. The only reality was my (adoptive) family and whatever future relationships I might build with my newfound genetic relatives.

Sliding doors. Infinite options may have preceded every decision we make (or that is made for us), but they all disappear in that moment when the train door closes and our life speeds forward. We can imagine alternative pasts, but they are unreal, and ultimately meaningless. What is real is the life that we have lived and all that will follow.