In fifth grade I was a perfect prepubescent mess. I had long black hair that I often tied into braids. I wore chunky glasses with purple-tinted plastic frames, and my favorite outfit, I regretfully recall, was a plaid maroon shirt with ruffles and burgundy culottes. I was especially young for my grade—I had skipped third grade and my birthday was in the summer, so I was at least a year or two younger than my classmates. I was beginning to notice how absolutely uncomfortable and awkward I was. The seeds of self-loathing had begun to bud in my head. I wondered if a boy could ever like a Chinese girl. I never spoke about these worries to anyone, especially not my parents, who had tried so hard to teach us to be proud of who we were and where we came from. I didn’t think they would understand.

In the 1970s, the population of Taylor, Michigan, was 90 percent white and about 9 percent black. Only about one percent was Asian; I figured my brothers, adopted from Korea, and I made up a notable part of that one percent.

My parents did what they could to try to make up for that isolation. They tried to give us some kind of Asian experience by hanging Asian art on the walls and hiring Asian babysitters. They bought me an Asian Raggedy Ann doll, as well as a black Raggedy Ann doll, which were my favorite toys for years. We ate Chinese food regularly and drove to Ann Arbor to get Korean bulgogi. They sent my brothers to Korean school, which the boys despised except for the meals and the Tae Kwon Do classes. My parents offered to send me to Chinese school, but I refused. Back then, we just wanted to be seen as American.

I used to curse being different in my journals and in my dreams at night. I overcompensated. I went out of my way to prove how American I was, making sure people heard me speak my perfect English. I was Little Miss Everything in high school, class president for three years, captain of the pom-pom team, and a member of almost every club that existed. I excelled at a lot of things: school, socializing, public speaking, organizing. I had a healthy family life and lots of friends.

[Expert Audio: Growing Up as a Transracial Adoptee: What Parents Need to Know]

Yet I was a tormented hypocrite. Outwardly I tried to ignore or make light of the stereotypes and slurs. I would defend my brothers, but I would never have dated an Asian guy. During high school, I resisted even hanging around Asians. I did have one half-Korean friend who was on the pom-pom squad with me, but that was enough. I still feel bad for not being nicer or getting to know the other Asian American in my high school classes. I was so worried that I would be automatically paired with him in the minds of friends that I kept my distance.

I watched the movie A Christmas Story, which I now find delightful, and felt hot and flushed during the part when, thanks to the neighbors’ dogs, the family is forced to go to a Chinese restaurant for dinner. I cringed when the Chinese staff could not sing “Fa-la-la-la-la” and could only say “Fa-ra-ra-ra-ra.”

That’s what they think of me, I thought. They think because I look like this, I talk like that.

I worried when friends wanted to fix me up.

“Do they know I’m Asian?” I asked anxiously, thinking that no one would possibly think I was attractive.

I got sick of people asking, “Where are you from?” And after hearing me answer, “Taylor, Michigan,” their asking, “No, where are you really from?” I’d tell people I wanted to be a journalist and they almost always asked, “Like Connie Chung?” I grew bitter about Connie during my young years. I am not unlike many of my Asian-American friends in this struggle, but I did not know that yet. Aside from Pat Morita, on Happy Days and The Karate Kid, there weren’t many Asian-American stars. I felt isolated, and that would not change until my final years of college. I didn’t discuss those feelings with my brothers or my parents until years later; I didn’t want them to think they had done anything wrong. It was my problem, and mine alone.

It wasn’t until my sophomore year at the University of Missouri in Columbia that I began to figure out that being different was okay, and one of the touchstone events was when I made my first Asian-American friend.

Her name was Tisha Narimatsu. She’d been born and raised in Honolulu, where more than half of the residents have some kind of Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Filipino, or other Asian blood. Tisha was half-Japanese, half-Chinese. The issue of race to her at college was something completely different; she had never been in the minority before. I liked that she seemed comfortable in her skin and thought she was the perfect candidate for an Asian partner in crime, after deciding, out of the blue, that I was ready for one. I pursued her friendship aggressively. I talked to her during class, asked for her number, and invited her out. I was like a kid with a crush. Tisha was used to a more polite, nonintrusive Asian style, and I scared her a little, but she went along with it. In the end, we became good friends. Mainly, we went to parties and bars, drank a lot of Bud Light, and met guys.

One night, after returning from happy hour, I made her stand in front of a mirror in my bedroom next to me, so I could compare our eye shape. I was a little buzzed and wanted to see if it was true that we looked alike, as so many white folks in Columbia said. Tisha humored me. I remember giggling as we stared at each other in the mirror. In fact, we did not look so alike. My eyes were bigger, more almond-shaped and slightly crooked. Hers were more even, a bit longer, shaped more like a thin slice of the moon. I had angular eyebrows; hers were more curved.

This firsthand proof—that all Asians, in fact, do not look alike—was one in a series of discoveries that might have been obvious to Tisha, my birth sisters, and others, but was not so apparent to me. At the same time, I was recruited, still reluctantly, into the first, and only, Asian-American group on campus back then. That first meeting was strange, all of us in one place. I remember nibbling the Korean cookies that someone brought and being ultra-aware of the Asian-ness of everyone in the room. I wondered what I had in common with them, besides our ancestors being from the same general continent, but I related to their tales of feeling harassed or isolated. I attended more meetings and began to forget about race: theirs and mine. I also got involved with the Asian American Journalists Association, through which I met a ton of incredibly smart and successful Asian Americans who defied the stereotypes.

By the time I graduated from college, I had figured out that I actually liked being Chinese-American, but I still tried to convince people—most of all, myself—that my past might have dictated what I looked like, but it would not determine who I was or would become.

Then I met my birth family and suddenly found myself trying to be Chinese.

*****

I love dumplings.

I have loved them ever since my parents used to take us to Chinese and other Asian restaurants. I adore their compact efficiency, how perfect they look on the plate, the burst of flavor in my mouth. I have savored sizzling guotie in a home restaurant in Kinmen, made by a grizzled woman who hovered over a crackling grill while her children pulled at her skirt. I have inhaled an inhuman number of shumai, hargou, and other types of dim sum in smudgy dining rooms in Hong Kong. My husband and I physically crave xiaolongbao, a perfect specimen of dumpling that is filled with soup, as well as the meat or seafood filling. To me, dumplings are almost an obsession.

What a joy it was to have access to a family who knew how to make, buy, and eat the best dumplings. That first morning I woke in Taipei, Min-Wei was eating dripping pork dumplings from a plastic bag, and offered me one, winning my heart forever. Fourth sister Jin-Hong later made shuijiao, boiled dumplings, for the entire family.

“Please teach me,” I begged, and she pleasantly agreed.

Jin-Hong and Ma took me to the local market, where we picked the handmade dumpling wrappers and the freshest cabbage, carrots, and pork meat. At home, my sister took me to the kitchen and led me through the steps.

First, you finely chop the pork meat into tiny pieces, and then the cabbage, even more finely. Make sure you squeeze out the excess water from the cut vegetables and the juice from the meat; the mixture has to be as dry as possible.

Jin-Hong opened the dumpling wrappers and placed one in my hand. They were light circles, floury and cool in the palm. She placed another wrapper in her slightly cupped left hand and put a dollop of the meat-vegetable mixture in the center. She folded the wrapper in half and pinched it together at the crest and she pulled delicately and quickly at the dough, folding forward tiny waves of wrapper until she had a perfect pregnant-looking crescent. I clumsily tried to imitate her fluid movements.

Dumpling-making is often a team sport, with the entire household participating. My other sisters, and even brothers-in-law, gathered around the table, joking, laughing. They filled and folded their lopsided dumplings and declared, “Mine is most beautiful!”

[“Beyond Fan Dances and Tea Ceremonies”]

When all the wrappers were used up, Jin-Hong showed me how to cook the shuijiao. She scooped out the result in a strainer, and tossed them steaming hot on a plate. They tasted fantastic, especially with soy sauce, vinegar, and chili sauce. They disappeared in seconds.

I mentally recorded Jin-Hong’s lesson and practiced it when I returned to the United States. Each time, I got better and better at making them. Wherever I lived, I sought out Chinese grocery stores, hunting down the best place to buy the wrappers and fresh ingredients. I mixed Chinese tradition with a few modern conveniences to satisfy my American impatience, buying the pork already ground and using a food processor to shred the cabbage.

I enjoy the ritual of making dumplings, the feel of the soft, malleable dough against my fingertips. It’s therapeutic to spend an hour folding in front of the television the afternoon before a party. Sometimes I invite girlfriends over to bond over dumpling-making. My dumplings are, to this day, the most popular dish at my dinner parties.

“You made these by hand?” people ask in wonder.

“Yes,” I say proudly.

“Where’d you learn?”

“My sisters,” I respond. And they nod approvingly, as if it must come naturally.

*****

Each time I visited, and each time my birth sisters visited me, I collected a little bit of vocabulary, history, habit, and tradition and tucked it away in my brain. I bought Chinese scrolls to decorate my home. I learned a few simple songs and dirty sayings. I can say “fart,” “drink beer,” and “make love” in Mandarin. I could sing funny little nursery rhymes. In Beijing I bargained in tiny shops for two traditional chipao dresses, embroidered silk with high mandarin collars and slits on the sides. I would wear those dresses on special occasions, including my wedding rehearsal dinner.

I copied some of my sisters’ styles. I saw, for example, that none of my sisters wore bangs, even though I’d always had them because I hated my forehead (I thought it was too high). Soon after I met the girls, however, I grew out my bangs and have not cut them since. I wore open-toed sandals and higher heels, like they did. I was proud of “looking Asian,” something I couldn’t have said merely five years before.

I was developing a new culture of my own, which neither set of parents had handed down to me. Certainly, I may have inherited a love for vegetables from my birth mother or a penchant for the dramatic from either one of my fathers, but the new habits and tastes I had begun to co-opt were not biologically mine, nor did they grow organically from my childhood. In fact, I was becoming the Asian American that people had always assumed I was, with a culture that came with the face.

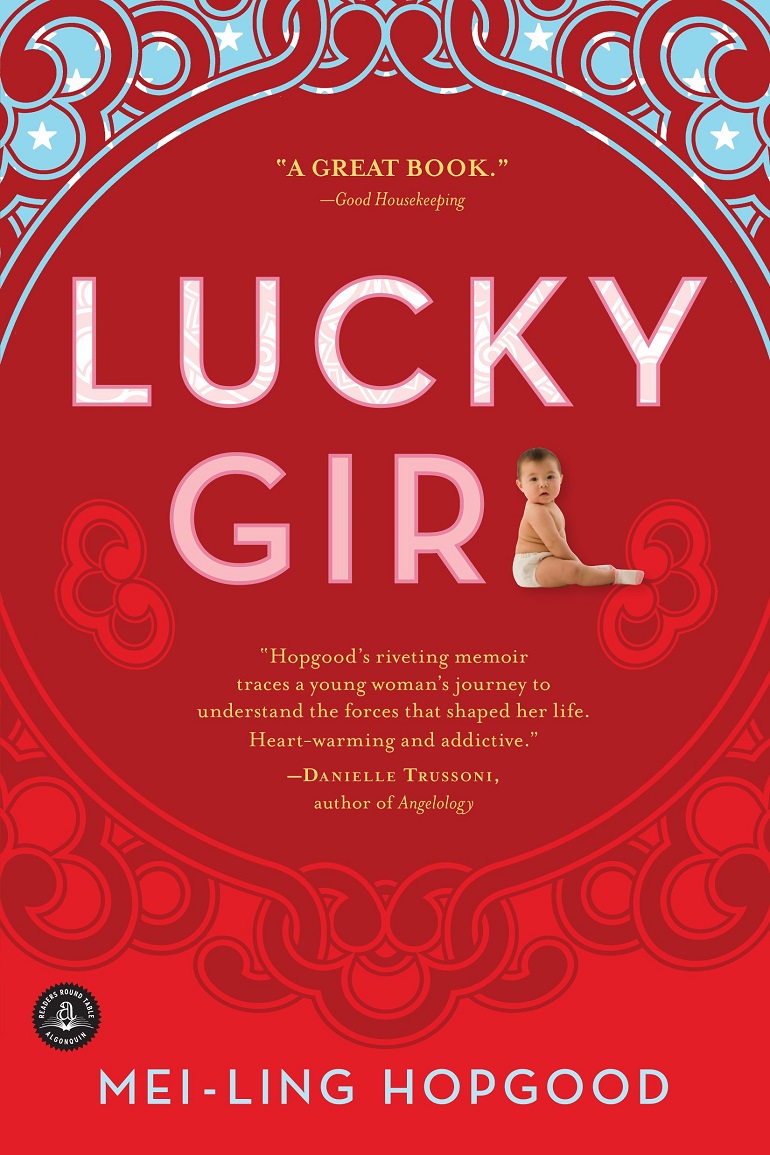

Excerpted from Lucky Girl, by Mei-ling Hopgood. Reprinted with permission, Algonquin Books.