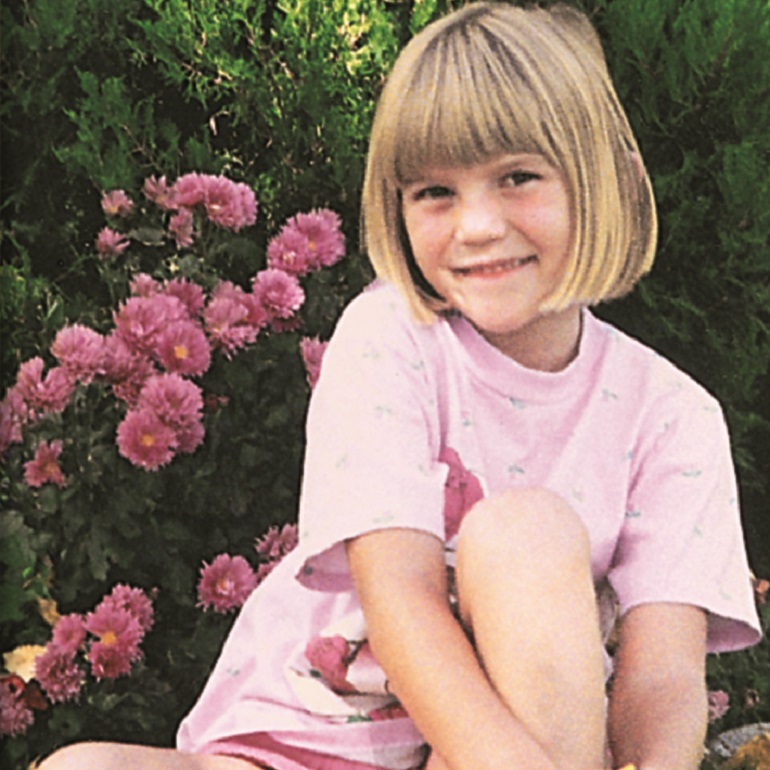

We watch Rose on videotape. A small, blonde waif sitting on the floor, arms wrapped around the back of her leg. She picks at her shoe, parks her gum on a tabletop, and smiles into the camera.

“I live on a farm. There are two kids there.” Her six-year-old voice makes two-syllable words out of “farm” and “there.”

“Starla is my sister and Jamie is my foster sister. Nancy and Fred are my Mom and Dad.” Making homes for her beloved “baby cats” ranks high on the preferred activity list. “If you guys…if…if…my new family lets me bring a baby cat, I’ll bring Sylvester. He’s the littlest one of all.” Rose’s dark eyes are alert and bright; she seems happy, for a kid in her seventh foster home.

“Do you know why were making this tape?” asks the social worker off-camera.

“Because you want my new family to see what I’m like?”

Foster mom Nancy briefs us: Rose likes strawberry yogurt, going barefoot, and plastic shoes called “jellies.” She loves to ride in the combine with foster father Fred and listen to Paul Harvey’s, “The Rest of the Story.” She yells cusswords down the toilet and wins the best student award in her kindergarten class. Her teacher plus 22 other families want to adopt her. Adams County chooses us.

Sizing Us Up

Rose is a fighter–a weed between concrete slabs. She and her sisters, Starla and Tina, have bonded through fear, affection, and a mother’s denial of sexual abuse by Dad and Uncle. They slept together in one saggy bed and ate rice and peanut butter when welfare checks ran out. She landed in state custody when an aunt’s conscience compelled her to report the abuse to authorities. On the sisters’ last visit with Dad in jail, Rose was the one who confronted him with, “Why did you do this to us?”

“She’s verbal,” says the social worker. “You never have to wonder what Rose is thinking.”

We meet her at the farm where she has thrived for 18 months. Before our visit, we’d sent a pink vinyl photo album with a handwritten, “Hi Rose!” peeking through the heart-shaped cover–the sum total of her new family in a dozen plastic sleeves.

We travel with two social workers–hers and ours. She and her sister whisper behind cupped hands. Rose gives me a hug, but steers clear of George.

Gathering for coffee and cake in the dining room, we discuss the half-day visit, the overnight, and the ultimate nine-day stay, a phase-in plan to help her adapt. She climbs on my lap, appraising me with watchful eyes. What does she make of metallic shoes and flowered socks?

“Now,” I think, “we’re starting this right now.” After years of planning, it is happening, and I feel insecure, a mix-and-pour Mom of recent and flimsy construction. What will I cook? Will Georges size-14 feet clomping down the hallway frighten her? I want this child, but I don’t love her yet. I mentally plan the purchase of her welcome-home gifts.

Memories and Shadows

A crisis occurs after the first visit, when Rose tells Nancy that George has a “look” just like biological Dad’s. Her biggest fear is out in the open: Will she be safe in our home?

Nancy suggests that we read A Very Touching Book with Rose, which we do while the social worker watches. The third kind of touching is called secret touching. It happens when an older, bigger person touches a child’s special parts and makes it a secret. Secret touching may happen with a person so…so…so…big and important that you feel too…too…too little to tell.

“We don’t allow any secret touching in our house,” we assure her.

George makes a series of exaggerated expressions while Rose tries to identify the look that scares her. He stretches his cheeks in a wide grin, pulls his lips forward like a chimpanzee, raises his eyebrows high. Doubts about her safety never come up again.

As I wander the toy store, memories rush in, rich with jump-rope rhymes, dolly layettes, and my sister, the only person in the world who knows the meaning of chucky-mucky and dopey-ni. I think of Rose, who will never collapse in laughter with a sister reading cereal boxes in froggy voices or making banana splits in a swimming pool.

“Excuse me, what do six-year-old girls like?” I ask a clerk wearing a bright teal apron and perky smile.

She marches me to the music section for a set of audiotapes with silly 50’s favorites like “Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weenie Yellow Polkadot Bikini” and “Purple People Eater.” I also pick a plastic tape player in primary colors.

I choose two colorful hardcovers, Pecos Bill and Amelia Bedelia and the Surprise Shower. Rose did not know what book meant before kindergarten. I hope she likes these. Crabtree & Evelyn is the final stop, for five drawer sachets tied with blue ribbons.

I am a fairy godmother, a mathematician canceling fractions, desperately trying to reduce everything on each side of the equation back to one so we can start over. Rose’s external life can change, I learn, but some of the sorrow underneath remains.

Finding Our Way

I pick her up from foster care for the last time 16 days after we met. Small and solemn, she stands in the doorway with clothes and stuffed animals packed in a cardboard box. Her sister has left for New Mexico to meet her new family. Rose is the last to leave the only safe home they ever shared.

First grade starts the next day, and new jeans, a denim shirt, and a patchwork vest are my picks for a well-turned-out first grader. Rose prefers soft pullovers, no buttons, but I don’t learn this until later.

She says, “I love you,” 15 times a day, and I echo back. At a Labor Day barbecue, her favorite game is ringing the back doorbell and running away. After the fifth time, George waits in the hallway and flashes a hand-held whoop alarm at her. A few minutes later, I find her crumpled in a ball, sobbing by the side of the house. She hides her fragility so well.

“Can you tell that I’ve been crying because I miss my Mom?” she asks me sometimes.

“Why, no,” I say, throat and stomach tightening.

In September it is still light after supper, so we go to the park three blocks away for Indian summer evenings. She rides a 1960’s one-speed bike in peacock blue, bumping across the soccer field, little legs pumping, fanny off the seat. We explore for treasures and sing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.”

“I’m hungry,” Rose says several times a day. We feed her whenever she asks, at 3:20, 4:45, or 10 minutes before dinner. She finally figures out that she will not go hungry in our home.

“Rose, do you remember anything about when you first came to live with us?” I ask.

“No.” she says.

A Bond Takes Hold

“Mom, you have to say ‘Jump down, spin around, pick a bale of cotton’ before you lift me out of the bathtub!” Rose demands. This becomes part of a complex after-bath ritual.

“John Jacob Jingleheimer Schmidt, tadadadadadada!” she shrieks after the fifth chorus, one of many car songs we belt out together.

Time and routine give us comfort. Rose is my baby, and I am as watchful as if she were a newborn, trying to find ways to bond.

“Mommy, will you rest with me?” she asks after we turn the lights out. Occasionally I fall asleep with her, and George rouses me to come to our bed. Our new family sprouts a hint of green on its stark, gray branches.

“I’m glad you are doing so well,” says the social worker. “Unfortunately, Tina and Starla’s new family hasn’t worked out.”

Rose is stunned. I can see it in her eyes. Two older sisters are back in foster care after a disrupted placement–another abandonment. Later, Tina’s foster mother decides to adopt Tina permanently. Starla is put back on the waiting list–but not for long.

And I thank God that my own daughter, once a tumbleweed, no longer needs to roll.