During the long months my husband, Dan, and I were waiting to adopt a baby, I often wondered how I would react when I finally held this child of our dreams.

Would I shed tears, like the weepy parents in media portrayals of hospital births? As it happened, I was grinning merrily on the day our beautiful daughter, Beth, just two days old, was put in my arms. I floated, giddy, as high as a kite; I did not cry.

There was a day, however, when the joyful tears flowed freely. That was the day Dan and I drove to a Maryland courthouse to finalize Beth’s adoption. I had not expected this to be a banner day. If anything, I was cranky and jittery on the spring morning that we buckled Beth into her car seat and fought our way through rush-hour traffic to an unfamiliar part of Montgomery County.

Would we find the courthouse? Would we arrive on time? Would my parents and my older brother know where to find us? Perhaps, too, there was a submerged fear: What if some sudden obstacle rose up at the last minute to impede this final, crucial step on our road to parenthood? Rationally, I knew this court appearance was routine, a mere formality. Yet I desperately wanted it to go well.

A memorable milestone

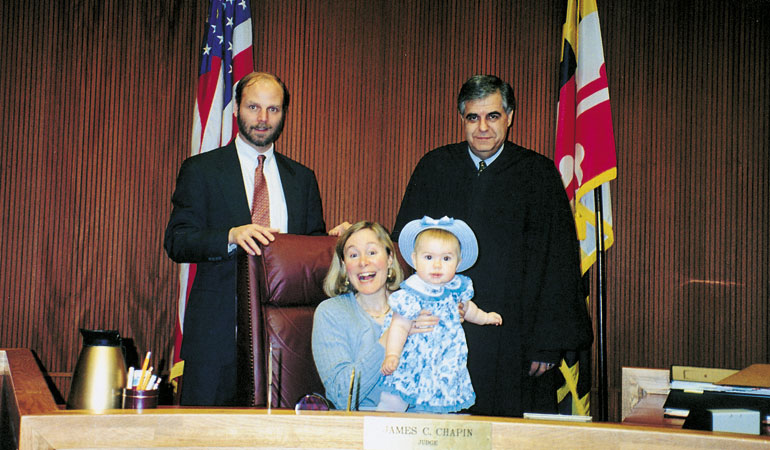

As it turned out, our finalization hearing before family court judge James C. Chapin was one of the more memorable milestones in our adoption journey. Genial and gray-haired, Chapin endeared himself to us immediately by making a fuss over Beth, then eight months old. Admittedly, she was looking adorable in the little blue-and-white flowered dress, complete with matching hat, that I had selected for the occasion.

“I can’t take my eyes off her,” he declared. The judge actually apologized for being too busy to invite us back into his chambers before the hearing — evidently his normal practice with adoption finalizations. Nonetheless, he went out of his way to acknowledge the happy significance of this day.

“Adoptions are a judge’s highlight,” Chapin told us, following introductions by our lawyer, Mark McDermott. “Family court is typically a place where people hash out disputes,” he continued, “but in adoption, everybody’s happy.”

Even the legalistic phase of the hearing was moving. It was surprisingly gratifying to hear Chapin intone authoritatively that the Court “finds that it is in the best interests of this child that this adoption be granted,” that “the child will now have the relationship of parent and child with Daniel and Elizabeth Carney.”

What Chapin said next left me wiping away those tears I had wondered about for so long. “It’s almost a shame that Beth is so young that she can’t really appreciate what’s going on,” he concluded, “because I always like to reflect on the fact that when we come into this world, we don’t pick our parents and our parents don’t pick us. It just happens. However, in adoption it’s a little different. The adopting parents so love the child that they go to a great deal of trouble to seek out the child, to have that child become theirs. I’m sure there’s nothing but wonderful family love ahead of you.”

A defining moment

To be sure, we were Beth’s parents, and she our beloved daughter, from the day we brought her home. In the eight months before going to court, we had delighted in her first smile, her first laugh, and in getting to know her better every day. The revocation period had come and gone. (Maryland law gives birth parents up to thirty days to revoke their consent to an adoptive placement).

Yet when we held the documents certifying us as Beth’s legal parents, I felt pride and relief. It’s a feeling shared by many adoptive parents on finalization day when the red tape is finally “unstuck,” as one adoptive mom recently described it.

“I think the finalization process helps adoptive parents feel legitimately the parents of the child,” says Ellen C. Singer, a social worker at the Center for Adoption Support and Education in Silver Spring, Maryland. “There’s the legal, and then there’s the emotional. Does the legal impact the emotional? I think it does.”

In some cases, says Singer, the finalization helps adoptive parents build a better relationship with their child’s birth parents. “Fear that the birth parents will regret their decision, and that the adoption will be put in jeopardy can make adopters reluctant to meet or communicate with birth parents,” Singer says. “Once the finalization has occurred, the parents are much more comfortable with contact.”

A birth mother’s relief

Arriving at finality and closure is important for birth parents as well. For most birth parents, the significant moment is not finalization, but the point when the revocation period ends. Jessica O’Connor-Petts, of Virginia, whose birth son, Brentan, is now three years old, was relieved when her state’s ten-day revocation period was over.

Still, O’Connor-Petts was keenly aware that Brentan’s adoptive parents did not yet have legal custody of him. She feared that, should something happen, he would be back in the legal custody of his adoption agency. “I didn’t know what say I would have in the next placement,” says O’Connor-Petts.

Brentan’s adoption finalization put those fears to rest, and his birth mother was genuinely happy for the new family, with whom she has maintained contact: “I was happy that it was final. He wasn’t going to go to any other home. This was it for him for the rest of his life.”

A new identity

I had known that, once our adoption was finalized, Beth would be issued a new birth certificate with our names on it. Early in the process, I had found this odd, even strangely deceptive. I looked into obtaining a copy of her original birth certificate, so that her records would be complete. But amid the excitement of being a new mom, I never followed through.

Fortunately, Maryland’s recently enacted open records law ensures that Beth, should she ever wish to, will have access to this document. Funnily, though, I no longer regard her “altered” birth certificate with ambivalence. In its own way, it tells the real story: We are a family, and she is our daughter.

I knew it in my heart the moment that I looked into her sweet face. Now I know it in my head. And now, the state of Maryland — even the U.S. government — recognizes it, too. It’s a small victory, perhaps. But it’s one that brings a quiet sigh of relief and maybe even a tear to the eye.