Over the past 25 years, I have parented four children through intercountry adoption, fostered eight, and supported hundreds of families and children as an adoption social worker. I hope each child and parent left my care stronger and better prepared for the potential of a successful future. I certainly grew with every experience.

When asked what they have learned from their kids, many parents say with a smirk, “Patience.” I hope that I have been patient with my children, at least most of the time. However, my children did not teach me patience; they demanded it. What they are teaching me is much more important, and I am learning far more from them than they will ever learn from me. In the sections that follow, I share some of these lessons, each one illustrated with a story or two written directly to my children.

Lesson 1: Expect the Unexpected

When I asked my children the most important lesson they have taught me, they agreed it was to expect the unexpected (and be OK with that). Each of us has plans, dreams, and hopes for our lives. The overwhelming majority of us envision ourselves one day parenting a child. Most families formed through adoption, however, found themselves unexpectedly unable to have a biological child. Infertility (or not having a partner) is the beginning of many twists and turns in the life plan of an adoptive family—through the process and into parenthood.

Many of us hold expectations for our dreamed-of child: she will be artistic, he will be funny, she will be athletic, he will be studious, she will be a leader, and so on—but who will our child really become? As adoptive parents, however, the mystery of our children’s genetics, birth history, and birth family heritage allows us the joy of discovery. Every day we learn more about who they are. We are also able to encourage them to become who they are meant to be without expectations.

Parenting through adoption and foster care necessitates us to rewrite the blueprint of our lives. It requires us to modify our life plan and alter our expectations. It also gives us the freedom to embrace the unexpected and, by doing so, enrich our lives beyond measure.

Two Care Packages

Marco, from Guatemala at 10 months of age

I had just finished graduate school and was working as a social worker in an adoption agency. I was parenting your two sisters, and we had recently moved into a new house and community. We were getting settled and I was comfortable in my life. Then an international placement agency my agency partnered with called about an older male infant from Guatemala. He was only nine months old, but this was considered older for Guatemalan adoption at the time. The agency asked if I could find a family for this child. I thought, this should be easy—but, after two months, I had not found a family who would adopt this little boy. So, I called the placement agency and told them that I would be his mom.

Everything was proceeding as planned. My paperwork was sailing through the government processes and it looked like Carlos would be home soon. A worker from the adoption agency was traveling to Guatemala, so she took a care package filled with toys, clothes, and books to Carlos’s foster home for me. I couldn’t wait to hear how Carlos was doing. But days after the worker’s visit I had still heard nothing. I wondered if something was wrong. Then a co-worker came to see me and told me that Carlos’s birth mother had returned and decided to parent. I was devastated. In my mind, Carlos was already my son. I respected his birth mother’s decision and was glad that Carlos was able to remain in his birth family. However, I was very sad that I would not be his mother. The excitement and anticipation of this unexpected adoption became the hurt of the unexpected loss of his adoption.

Very soon after, and again very unexpectedly, someone called and said that they had another little boy who needed a family. They explained that he may have been born early, but they did not know for sure. All they knew was that he weighed only five pounds at one month old. The agency sent me pictures of you, and you were adorable. I quickly said yes and began paper chasing again. I put together another care package filled with clothes, toys, books, and a blanket, and sent it to your foster family. Your foster mother sent me back pictures of you surrounded by the toys and wearing the clothes. Every month, I received new pictures of you and a quick medical update. You were growing up too fast. I desperately wanted you home. Seven months later, after many paperwork glitches, governmental regulatory changes, unexplained delays, and the U.S. threatening to close down adoption in Guatemala, you arrived safely home the week after Easter. You were one of the last children permitted out of Guatemala before the U.S. closed to intercountry adoption from your birth country.

I still think of Carlos and hope he and his family are well. I always thank Carlos for bringing us together. My unplanned adoption of Carlos became my unexpected adoption of you.

Lesson 2: Trust Leads to Bonding

As I prepared to meet each of my children for the first time, I was excited but anxious, confident but uncertain, controlled but emotional, frightened but calm, worried but filled with hope, and happy but sad for the losses that created this adoption. Each time, through this sea of emotions, my child was placed into my arms for the first time.

In that same moment, my child was placed into the arms of a stranger: My arms. The child I was desperate to love and be loved by was now on my lap crying, hitting, kicking, and trying to escape my embrace or, in one case, unresponsive in my arms. Who was I and where did his first “mommy” go? I didn’t look like her beloved caregiver from the orphanage or foster home. I didn’t speak his language. I’m sure that I smelled funny and ate weird foods. In that moment, each of my children lost everything they had ever known. They must have been confused, terrified, anxious, grief-stricken, and distressed.

I learned to be patient. My new child and I were strangers. We needed time to get to know each other and to build a bond. Most people believe that attachment between parent and child comes from love. While attachment results in the feelings of love and bonding, it must grow from trust. A child only becomes attached to you after you have repeatedly met his or her physical, emotional, and social needs. Luckily, children have needs all day every day, so you have thousands of opportunities to satisfy your child’s needs and earn their trust. When my children are hungry, they need to know that I will always feed them. If my children are tired, they need to be assured that I will help them calm down and rest. When my children are frightened, they need to be confident that I will chase away the scary monsters in their closet before bed each night. When my teenager struggles to get a project done on time, she needs to believe that I will be patient, understanding, and encouraging.

Most foster and adoptive parents expect that they will instantaneously become bonded with their new child, but this, too, is unrealistic. We need our children to need us, and we need to become confident in our ability to meet our child’s needs. We need to experience feelings of accomplishment, competency, and fulfillment in parenting. We need to experience joyful feelings as our children give us positive feedback with a smile, a hug, giggles, a thank you, a joke. Attachment is a process and takes time for both the child and the parent.

Mom Be Back

Wu LeBin, adopted from China at almost 8 years of age

You had been home for exactly one year after I adopted you from an orphanage in the People’s Republic of China. Your grandmother was visiting for a week and she was caring for you for a short time so that I could take your brother to an eye doctor’s appointment. I typically took you everywhere I went, but you were not able to go to your brother’s appointment. At almost nine years old, you had very little language, and, as a result of autism and cognitive deficits, you had the social/emotional skills of a toddler. Before I left I told you I would be back and I gave you a fist bump.

For the first 10 months after your adoption, you were glued to my side. You never let me out of view and wherever I went you followed. If you were able to anticipate my movement—for example, going upstairs to bed—you quickly darted in front of me to make sure you weren’t left behind. If one of your siblings or I put on shoes or a coat, you immediately ran to throw on your coat and boots. You always beat us to the car. You were petrified that we were going to leave you behind. If I had to leave you with your grandma or your aunt you would protest, scream, cry, kick, hit, pound your fist, and run after me. One morning when I had to leave you for a short time, your grandmother said you hit the dining room window with your fists so hard she thought it would break. Your grandmother and aunt (the only two people I could leave you with), told me that you would eventually settle down after 30 minutes.

I always came back. Whenever I returned, rather than greeting me with smiles and hugs, you would throw your body on the floor face down, cry, and kick your feet. Boy, were you mad! You were not able to verbally communicate with us. And I am assuming that you were overwhelmed and confused by your mix of emotions regarding my leaving and my return. Luckily, you were obsessed with cars, trucks, and buses, so you loved the school bus and gladly went to school.

A year after your adoption, and after hundreds of separations and reunions, I had to take your brother to another doctor’s appointment. You were playing at the dining room table with Legos® when your brother and I got on our shoes and coat. You hopped up to get your coat and race to the car. I told you that you had to stay with Grandma and that I would be back. I guided you back to the table and gave you our habitual fist bump goodbye. You returned to your project and said “Bye.” No crying, no fighting, no running after us—wow! Could it be that after a year, you finally trusted that I always come back?

Two hours later, we returned. I was expecting an emotional scene, but there was none. I greeted you and prompted you to say, “Hi, Mom.” You repeated, “Hi, Mom,” and continued to put together your Lego® truck. Grandma explained that you did not fuss or cry while I was gone. She told me that, about 30 minutes before we got home, you were sitting at the dining room table, still engrossed in constructing Lego® cars, when she heard you quietly say to yourself, “Mom be back.” You finally trusted that I would be back. After a year I could finally say that you were attached.

Lesson 3: Play and Giggle

When I adopted my youngest son just before his eighth birthday from a Chinese orphanage, he could only say a few Mandarin phrases. His favorite was 我要玩 (wǒ xiǎng wán ): “I want to play.” With this, however, he knew the most important words of childhood. Every child should have the opportunity to play and laugh. But whether they survived an abusive or neglectful home or lived in a sterile institution, many of our children were deprived of play and joy in their early lives.

For some, “playing” is something they need to learn how to do. My second daughter had never seen a toy prior to her adoption. Her orphanage was very clean and orderly, but was devoid of any toys, music, or books. In China, her aunt and I took her to the playroom at the hotel every day. At first she was uninterested, or more likely, overwhelmed. She watched, over and over for days, as her aunt pushed the buttons and switched the levers to pop up farm animals hidden under trap doors. Finally she reached out and grabbed onto the yellow chick that popped up and we rejoiced.

As we teach our children to play and be joyful, our children teach us how to play. Parenting should be fun and give us joy. Otherwise why would anyone parent? It is hard work. Watching my children play gives me great joy, and playing with my kids lets me share in the fun. Listening to my daughter play her trumpet in the band concert often fills my eyes with happy tears. Getting beat at Chinese checkers by my daughters (and their grandmother) is infuriating but also tons of fun. Watching my son jump up and down with his hands in the air after bowling a strike fills me with excitement and happiness. Cheering my daughter on as she rounds third base for home gives me great delight. Having tickle fights, pillow fights, and pretend karate fights give us all the giggles. Our children help us find joy in parenting through play and laughter.

Shoes on the Car Roof

Lisa, fostered newborn to 18 months of age

A Child Protective Services caseworker called me a week before Christmas, and asked if I would foster a school-aged boy, an 18-month-old girl, and a little girl yet to be born: That was you! Your brother and sister arrived a few days before the holiday. A week after the New Year, your caseworker called me at work and told me that I was to pick you up at the hospital right now. I did not even know you had been born! I quickly left my meeting and ran to the store to buy supplies.

You were my first newborn child and I knew very little about taking care of an infant, but the nurses entrusted you to my care with the briefest of discharge instructions. I have to admit, it was a little scary and very intimidating. You were tiny (only six pounds at birth), but beautiful, and you were a very easy baby, thank goodness. I quickly learned how to care for you and we both grew and developed.

A few months later, on a frigid and snowy winter morning, I had an important meeting at work first thing in the morning (or what I perceived as an important meeting at that time). You and your sister went to childcare while I worked and we were rushing to get out the door after getting your older brother on the bus to school. Your childcare provider was only two blocks away, but it was too cold to walk, so I cleaned your spit-up off my suit jacket, put on my coat, and slipped on my snow boots. As your sister toddled ahead of us, I carried you, your diaper bag, my brief case, and my dress shoes to the car.

As I unbundled you and your sister in the foyer of the child care home, the childcare provider peeked outside and told me that my dress shoes were on the roof of my car. Oh, my! She and I laughed until we cried.

It had been a very stressful few months, with the sudden placement of you and your siblings into my home while I was working full time. Giggling over those ridiculous shoes on my car roof was the therapy I needed. Even now, 20 years later, I always make sure that my dress shoes are inside the car before I drive off, and I giggle to myself as I do it.

Lesson 4: Birth Families Are Forever

Every adopted/foster child has two sets of parents: birth parents and adoptive/foster parents. It is often said that birth parents give the child life and the adoptive parents give the child a life. This is true, but simplistic. Regardless of your personal beliefs around nature versus nurture, your child’s genetics, prenatal environment, and birth history set the framework for who your child is and will become. These factors shape your child throughout her lifetime—the color of her eyes, her predisposition to diseases, personality traits, body type and size, learning capabilities, physical abilities, and more. Was she nourished properly in utero? Exposed to alcohol or drugs? Was she born early? Withdrawing from drugs? Whether or not we know this information, the influence remains.

Most children who enter foster care or who are adopted do not join their families at birth. Your child may come into your family after being abandoned by their birth parents and cared for in a foreign orphanage or after being abused or neglected in their birth family for months or even years. Your child’s history of institutional care, abuse, and neglect also has an impact. Our children’s birth families also shape the lives of our children as they yearn to understand themselves. They wonder who they look like and whether they share any traits, talents, or quirks with their birth parents. They think about their birth parents, their birth heritage and culture, their racial composition, and their genetic ancestry as they work to form their identity.

Your child’s birth family is ever-present and forever a part of your child and family.

I Wish You Knew

Rose, adopted from China at 11 months of age

You were about eight years old when you asked about your birth parents during dinner one night. We talked about how hard it was to not know. We wondered, “Did they look like you? Do they have fun personalities? What do they do for work? What are their hobbies? Do they have any interesting talents? What are their quirks?” I wish we knew.

You, however, wished they knew you. You told me that you wanted to know your birth parents because you wanted them to know that you are happy and growing into an amazing young lady. You wanted to assure them that you are safe and loved. You were able to understand that, just as you will never know your birth parents, your birth parents will never have the joy of knowing you. You appreciated that your birth parents will forever wonder if you were found and brought somewhere safe (they abandoned you at the crossing of West Street). They don’t even know that you are alive and thriving. They don’t know that you have a mommy, a sister, and two brothers, that you are excelling in school, that you play the trumpet and piano, that you volunteer at school and in your community, that you are a good friend, and that you are silly and fun. They must also yearn to know if you look like them, if you have a personality similar to theirs, if you excel in the same school subjects as they did, if you enjoy hobbies like theirs, if your talents came from them, and if you have their quirks. Your wish was for your birth parents to know you, to gift your birth parents with peace of mind.

**

Author’s note: My foster children’s names have been changed and their stories have been altered slightly to protect each child’s identity. My children through adoption have given me permission to write their stories and use their names. They have read and agreed with the content and intent of each story.

Author’s note: My foster children’s names have been changed and their stories have been altered slightly to protect each child’s identity. My children through adoption have given me permission to write their stories and use their names. They have read and agreed with the content and intent of each story.

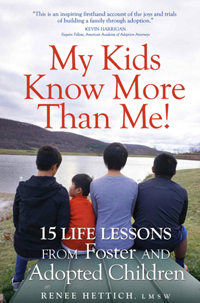

Renee Hettich, LMSW, is the author of My Kids Know More Than Me! 15 Life Lessons from Foster and Adopted Children, from which this article was adapted with permission, and the AGAPE Southern Tier-Finger Lakes Director at the Adoptive and Foster Family Coalition of New York (AFFCNY). She is the mother of four children adopted internationally and one child who recently joined their family through kinship care.