I was 46 when I adopted Amelia. Most of my peers have college-age children; many of them are grandparents. Like others my age, I’ve lost a parent and a few friends. But until now, I have not thought of myself as particularly fragile; adopting as an older parent did not worry me. I have nice big bones. I walk two miles a day, and I have even begun to take calcium and daily vitamins. I’m used to feeling tired all the time, but I get through the days intact.

Today, however, I lie on the sofa watching a documentary about elephants. My left arm is in a sling, and whenever I move, it hurts. I cradle it across my chest. Elephants lumber across the screen, jostling each other. I learn that they communicate through smell and touch and gesture, through trumpet sounds and low rumbles inaudible to the human ear. I learn that they are shortsighted. The camera offers an elephant’s-eye view of the world, which resembles my own when I take off my glasses.

My seven-year-old daughter is at school. I’m at home with a broken shoulder.

My very aged mother calls. I tell her I’ve broken my shoulder. “But I’m really fine.” I don’t want her to be concerned. I don’t want to field endless worried calls from her. She does call back an hour later, but she has already forgotten. For some reason, I remind her. There is an odd, distant pause.

“Oh, well,” she says, “you might have broken your neck.” I have no idea what to say.

Amelia arrives mid-afternoon. She has heard the news and she bursts into the room with excitement. “Mom broke her arm! Mom broke her arm!” By this time I have sampled the painkillers.

“You’ll have to help out a lot,” I mumble after she has examined my sling. Perhaps I can turn this accident into a Learning Experience. A lesson in self-reliance, an exercise in family cooperation.

I remember helping my mother put on her stockings on one of my infrequent visits last year. So ancient those legs, the skin so loose over the thigh. Ankles swollen, toenails grown long and yellow. I should have offered to cut them. I should be wracked with guilt. My relationship with my mother is not all that it might be. I hope that Amelia won’t mind helping me dress.

It is not easy putting on someone else’s sock. The next morning Amelia drapes one awkwardly in the vicinity of my foot, and I regret that she doesn’t like to play with dolls, even regret that we threw away the Barbie a classmate gave her for her birthday. We stare at the dangling sock and at my arm hanging uselessly at my side, then we collapse in laughter. Collapsing with laughing produces an electric shock of pain, but I bite my tongue to keep from crying out.

My mother calls in the evening. “Where am I?” she wants to know.

“You’re in New York,” I say. “On 86th Street.”

“Why isn’t your father here?” she asks.

“Mom,” I say gently, “Dad died eight years ago.”

“Where is my mother?” she asks. “I want to call her.”

“Mom,” I say patiently, “she died 30 years ago.”

It is time for Amelia’s bath. I sit on the closed lid of the toilet to keep her company. The lid shifts under my weight, my body twists a fraction, and then I scream. The sound is cinematic. I leave the bathroom and whimper in the hall. When I come back, my daughter is hiding behind the shower curtain.

“I never knew I could scream as loud as you! Ha, ha!” I try to turn this into a merry joke. But when I look into my daughter’s eyes, I see them shutter over in fear.

“I’m cold,” she complains, clambering out of the bath. One-handed, I try to drape a towel over her. It falls off. I can’t bend over to pick it up.

“I’m wet,” she complains. I want to fold her in my arms but I can’t.

This is a hard evening.

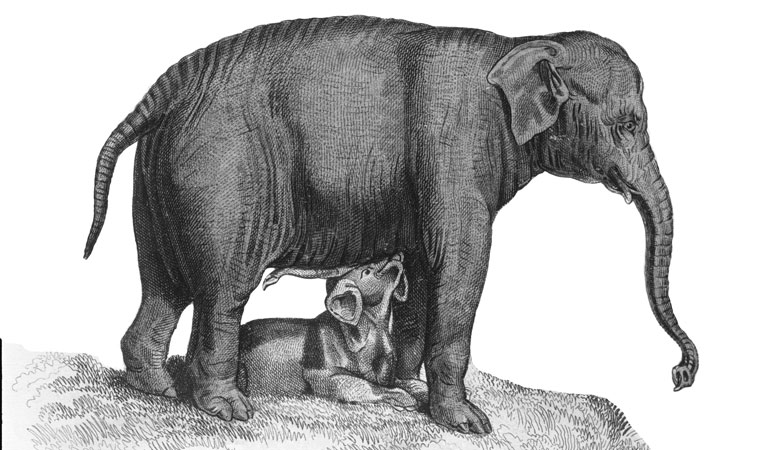

The doctor demonstrates my first passive therapeutic exercise, leaning over with his arm hanging straight down, swinging it in slow circles. He looks like a baby elephant struggling to control its trunk. The elephant trunk, I now know, is an amazing structure made up of over 1000 muscles. It takes years to master its functions.

Lesson one. A young elephant studies the ground — and whatever it is he’d like to pick up. Then he swings his trunk in little circles. The circles grow wider and faster; he almost tips over with centripetal force. He tries again. This time he manages to grab at a patch of mud and grass, and aims the tip of his trunk in the direction of his mouth. But he misses, flinging the whole mess into his left ear.

I lean over and study the floor. My arm begins to swing. I start to giggle helplessly. “Ouch!” I say.

“You’re coddling yourself,” the doctor tells me. “Swing wider!”

My mother calls. “I love you,” she says. “I miss you. You never call me.”

“I love you too,” say I.

“I hope I see you again,” she says.

This is exactly what my old aunt said to me the day before she died. Words tumble out. Soon, soon, I say frantically. In just a few weeks. “As soon as I can drive,” I tell her, “we will come.”

“We?” she asks, puzzled. “Who is ‘we'”

She has forgotten I have a child.

I have graduated from the doctor’s office to the Physical Therapy room. There I see a young woman I recognize. She had been in a terrible car accident and was in a coma for months. She is practicing walking without a cane, and they have provided a mirror for her to watch her own uneven progress. She looks almost unbearably happy.

I am witnessing a state of grace, I think, as I watch her shuffle slowly along. At the very least, here is the quintessential lesson in counting your blessings.

I have heard how close she was to death. How her mother sat at the bedside, day after day, month after month, stroking her daughter’s shattered body and whispering prayers.

Elephants again. If one family member is sick, the others will watch over her for days, touching her constantly with their trunks. If a mother dies, the others in the group will adopt her child. If they encounter piles of broken skeletons, they will sort through them carefully.

No one is sure how they recognize the windblown bones of relatives, but they do. They will pick up the bones and carry them for miles, balanced on their long tusks. Their memory transcends death itself.

I struggle to extend my aching left arm, worry mixing with this temporary pain. What kind of family are we? I’ve taken care to ensure that my daughter has a sense of community. She has a father figure who visits regularly. An array of cousins of all ages, although we rarely see them. But in truth, our relatives are scattered to the winds.

At the center is me. Mom, 53 years old, who would carry her daughter to the ends of the earth. A mom who, by the way, should get a bone density test soon. Mom has been lucky. She did not break her neck.

That afternoon, I wrap my good arm around my daughter like a big old trunk. I count my blessings. I call my mother before I forget.