Does your family follow rituals or traditions?

Certain activities that you repeat for each holiday or birthday or a particular day of the week?

Being “king or queen” for a birthday, eating special foods on holidays, attending regular church services — whether you realize it or not, each of these are family traditions. And no matter what your particular family traditions are, one thing is for sure: traditions make families stronger.

Rituals and traditions give family members a sense of belonging. They give predictability and order to life. To a child, they signal security and family pride.

Whether it’s a big Sunday dinner, a vacation to the same spot every year, or sitting in the old rocker to read bedtime stories, every time you practice a tradition, you are giving your child a stronger sense of himself. A Syracuse University study revealed that adolescents whose families enjoyed active traditions had more confidence and self-esteem and made easier adjustments during the transition to college.

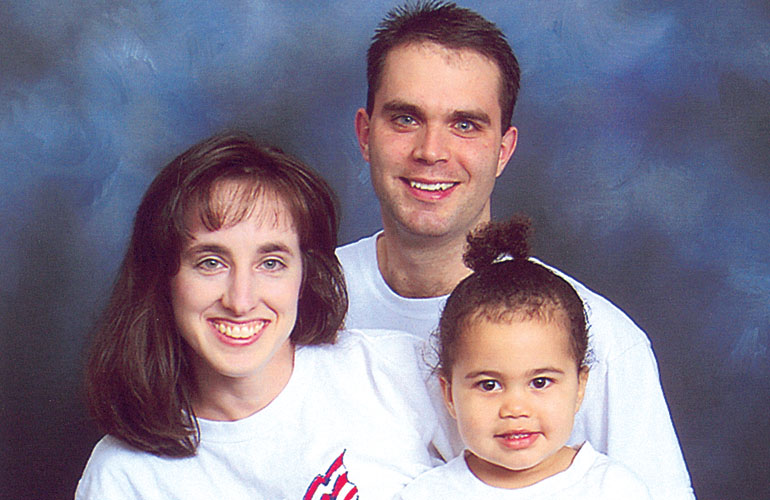

For multi-cultural families, options include creating traditions from multiple cultures, as well as those that are just unique to your family. Traditions can be based on your or your child’s ethnic heritage (Chinese New Year, Kwanzaa, St. Patrick’s Day, Fourth of July); on your religion (Easter, Hanukkah); your region (local festivals, an annual beach or mountain trip); your schedule (Saturday morning breakfasts, Friday night pizza); or your family history (anniversaries, birthdays, adoption days).

Traditions not only foster a child’s sense of belonging, they can also serve as valuable tools for instruction in values. Traditions show children how to live values and incorporate them into their lives. If you analyze many traditions you find that generosity, self-control, respect, kindness, compassion, and faith play a part. As parents we can consciously assure that the values we find important are incorporated into our family celebrations.

Make sure that the traditions you choose are ones that the whole family enjoys. Let children participate in planning, or creating their own special part of the event. Observe your family during these special occasions to see what parts mean the most to them.

You don’t need to to create the perfect time for everyone. What you do is not as important as doing something as a family, something than be repeated time and again. Creating your own family rituals now, and faithfully repeating them, will provide your child with a sense of rich family history, memories, and values that he will duplicate when he has his own family.

A friend told me a touching story about a recent Thanksgiving. They had many guests to dinner that year, so my friend decided to make things easier by slicing the turkey in the kitchen, instead of, as usual, at the table. As she did so, her oldest son cried out, “Mom, what are you doing?”

She explained, and his anguished response was, “You just ruined my Thanksgiving! You’re supposed to bring the turkey out on the platter with all the little leafy stuff around it, then you place it on the table, and then Dad stands up and carves it!”

Of course, her son recovered, but I don’t think they repeated the mistake of changing that tradition again.

–Lisa McColm

Chicken Feet for Thanksgiving

As vegetarians, our family usually enjoys a nontraditional feast for Thanksgiving. A typical Thanksgiving dinner for us would consist of meatless lasagna, a vegetable, salad, and pumpkin pie.

Last August, my husband, Pete, and I adopted two teenage siblings, Matthew and Sara, from Urumqi in Xinjiang Province, China. They like to eat meat, and we don’t discourage them.

This year we decided to let Matthew and Sara experience their first “true” Thanksgiving dinner. When we told them that we were going to prepare a turkey, they shook their heads in horror and explained that they were afraid of the turkey. So we put our heads together to decide our menu.

Matthew and Pete agreed to make a Chinese dish, Sara (with Pete’s help) would make a sweet potato casserole, and I would steam rice and make pumpkin bread and pumpkin pie. Pete and I have acquired a taste for Chinese food, so this menu sounded quite good to us.

At the last minute though, Matthew said there was one additional dish he would like to have — chicken feet! He explained that chicken feet are a delicacy in China. At this point, Jenna, our six-year-old, chimed in and declared that she had enjoyed chicken feet, too. (She was four when we adopted her from China.) She wanted to try them again.

Well, what could I say? As long as Matthew agreed to make them (he promised me that they wouldn’t smell while cooking), I figured the least I could do was to go along. But no way would I agree to eat them.

Pete found chicken feet at a local Chinese market. They were so large, he only bought six. On Thanksgiving morning, we all went about our tasks. Matthew wasn’t quite sure how to cook the chicken feet. We decided to boil them and add Chinese spices as they boiled. For those of you who have never seen cooked chicken feet, let me tell you that they expand when cooked. Six chicken feet filled a three-quart saucepan! I should also mention that the claws are on the feet when you buy them.

All the food was placed on the table, and we sat down to eat our first Thanksgiving meal since becoming a family of six. Five-year-old Maia (also adopted from China), a vegetarian like us, took one look at the chicken feet and said that she thought she was going to throw up.

When Jenna saw them, her eyes got as big as saucers, and she said, “Mommy, do I really have to eat them?” Meanwhile, Matthew and Sara began piling chicken feet on their plates. There is definitely an art to eating them. Matthew put the claw in his mouth, pulled it out of the foot, and spit it onto his plate!

We are not sure whether the feet were too spicy or just not cooked correctly, but Sara only ate one and Matthew, two. For some reason, the bowl of feet ended up next to my plate. Every time I looked down at my rice and vegetables, all I could see were those long-toed feet! After three bites, I had to put tinfoil over the dish.

Other than the chicken feet, our Thanksgiving meal was a success. Before we try chicken feet again (and I hope it’s not for a long, long time), we’ll find a recipe for cooking them properly. As I gazed around the table, I realized that this Thanksgiving we truly do have so much to be thankful for.

–Kristin Castiglione

Our Christening Day

While I possessed a secure sense of family life, my daughter Eva, adopted from the Ukraine at age three, had no idea of what family life meant. She had never even seen a family in the years she lived in the children’s home. She just saw a stream of caregiving women coming and going.

Although I knew that, legally and emotionally, I would be her mother forever, I hungered for a religious blessing on our little family and on Eva’s name. I knew that the source of my yearning was more than emotional. I sought God’s blessing on our bond for all eternity, something the INS cannot give.

As with a marriage ceremony, I sought a public declaration before God for being Eva’s forever mother and for Eva being my forever daughter. Since she had been baptized in her birth country, my minister fashioned a christening ceremony for us.

On the morning of Mother’s Day, I picked azaleas from our yard and dressed Eva in her pastel-flowered birthday dress (she had just celebrated her fourth birthday). Combing her dark blonde hair, I noted that not only was it longer than when I brought her home, but now the patchy, dull growth was thick and lustrous. In four months, she had grown two inches. The sheer responsibility and rewards of parenting swept over me.

We packed the confections and cookies (representing our combined Ukranian and Swedish cultures) into the car, along with flowers, matruschkas and painted wooden eggs. Eva thought we were merely bound for church and that something special would happen there. Perhaps she thought we would celebrate her birthday again.

But my thoughts on the way to Bethany Covenant church were of my mother’s parents, Andrew and Ida Carlson, pillars of this church in which they raised three children, including my mother. Today, their great-granddaughter — their daughter’s namesake — would be christened here. The sense of legacy was profound.

After we delivered the goodies to the ladies arranging the reception, we took our seats in the sanctuary, alongside Aunt Marion and cousin Richard, who were to be Eva’s godparents. My mind flashed memories of holding my mother’s hand while walking into this church every Sunday. Then came memories of Mom herself, and of my Dad, neither of whom had the chance to meet their granddaughter.

The worship service began. When the moment of the christening ceremony arrived, Eva walked to the pulpit with me. “Have you ever had an idea that never goes away?” I asked the congregation.

“Throughout my childhood, I wanted to be a mother, a blessing that marriage did not bring me.” All was flowing nicely until I began to describe the moment when I first saw my daughter. Tears clouded my vision and my throat tightened as joy choked the words midway.

Quietly Eva had left the minister’s side and was standing to my right, looking up at me. I asked her if she wanted me to pick her up, and she nodded. I held her for the rest of the ceremony. I explained that although many doors seemed to close during my quest for this child, in the end, we found each other.

The christening ceremony followed my remarks. By the time Eva and I resumed our seats, I felt that all was well in our world and in my heart. Christening my daughter on Mother’s Day indeed blessed her and us both as a family.

–Kristen Widham

A Bridge of Love

Rituals celebrating the birth of a child are among the most ancient and universal of all human ceremonial acts. And as adoption has emerged from the shadows of secrecy, these traditions have been adapted to reflect the joys of adoption as well. Yet for all their similarities, adoption is different from birth. The meaningful difference, one that remains largely unspoken, is the legacy of loss on which adoptions are founded.

Yet to deny that loss does not undo or even ease its power. It’s better, I think, to acknowledge its existence with a ritual of recognition and acceptance. I think that for adoptive families, it is especially valuable to create and engage in an entrustment ceremony to acknowledge, honor and mourn the losses that preceded your union with your adopted child.

Such ceremonies are relatively uncommon, there are few models to be found, and the task of creating one’s own can be painful and difficult. But if one of the greatest responsibilities of parenthood is to help our children find their way through the challenges of their lives, then the entrustment ceremony is an essential place to embark on our lives as adoptive parents.

Of all those involved in our son’s adoption, I was the one most convinced of the importance of creating such a ceremony. In fact, when I was writing it, a friend wondered why I was so explicit about grief instead of emphasizing the “good” things. I was vulnerable to that question then, but never since.

For the act of entrustment was not a happy occasion. Of course the baby’s birth parents were relieved that we seemed like a good family and that we promised to keep in touch. But even that glimmer of relief was tempered by the fact that they couldn’t know whether we’d be true to our word, whether they would ever see or hear of their son again.

Engaging in our entrustment ceremony was perhaps the most difficult experience I have ever had. The baby’s birth parents were in a state of grief, and the ceremony provided a place for the expression of that grief. Fortunately, we had asked the hospital chaplain to preside over the ceremony, for without her, none of us could have made it. With measured gravity, she read the words I had written, comforting the birth parents with her tone and gestures while at the same time, her serious demeanor seemed to authorize us to claim him as our child.

Near the end, our older son rushed to me and said in a cracked voice, “Mommy, we can’t take the baby; it will hurt them too much.” And I turned to the birth mother and said, “Elliott is afraid that we shouldn’t take the baby because it will hurt you. Can you please tell him what you want us to do?”

And she — bless her wonderful heart — turned to him with tears streaming down her face and said, “Baby, we need you to take him and be his brother. Will you please do that for us?”

The question of how to include older children in this experience can be difficult to answer. In our case, despite — or because of — our son’s sensitivity, we felt that it was important to have him serve as a memory-holder for his little brother. Include the children and have them engage in some enduring element of the event. Include their names in the ceremony; photograph them with the baby; have them make a memento or a gift for the birth parents and baby.

The role of birth parents is also one that will have to be determined by each family. The critical issue to me, is to recognize that the existence of these two people — and of their separation from the child they brought into the world — are the fundamental elements of this child’s earliest history. Therefore, this ritual must include the birth parents, whether in the flesh or only in spirit.

As an act of compassion and connection, I made keepsake boxes for the birth parents. Among other items, each box contained the text of the ceremony, our names and address, and a pre-paid phone card. If a birth parent is absent, you can create a keepsake to be held in trust.

I structured the ceremony to begin with our joint act of giving him the names we had chosen together. Only after joining together in naming this little person did we then undertake the ceremony marking his transition from their arms to ours.

When the adoption finalization came six months later, I found I needed another kind of gathering, one that celebrated our son’s arrival. On finalization day, his birth parents were again in our hearts. Our son wore a guardian-angel pin his birth mother had sent; we read aloud a letter they had written. And when the finalization was concluded, I called his birth mother.

“You and I made a bridge,” she told me through our tears. “And you know what? He was never alone on that bridge; I got him halfway across, and then you were there to take him home.” And the entrustment was there to remind us all that we were in this together, for the sake of this little boy we all love.

–Rebecca Weller