When I was a little girl, I used to give birth to my doll Kate several times a day as I let her fall out from under my T-shirt. Careful to support the baby’s head, I’d pick her up and stick a little plastic bottle filled with pretend milk to her lips. That was 35 years ago, and as close as I ever came to giving birth.

Let’s face it. Few women grow up wanting to be an adoptive mother. Little girls don’t act out scenes in orphanages or airports. They, like the women they become, assume that they will one day marry a handsome man and make beautiful babies.

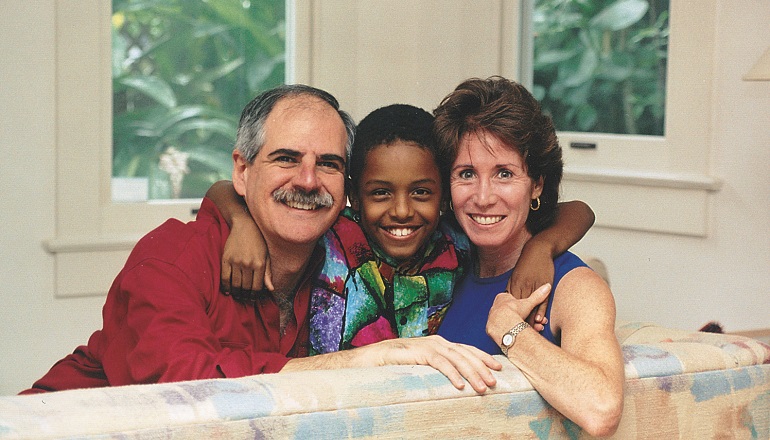

Adoption is not in the repertoire of child’s play. And it’s an experience for which we, as adults, are woefully unprepared. As my husband and I went through the process of an open, transracial adoption, I sensed that I was on uncharted ground emotionally, with no road maps or role models. I was having feelings that weren’t the kind I had read about anywhere.

More than just feeling “happy” and “sad,” I found the process almost surreal–is this my life? It was funny at times, and scary, too; familiar in some ways and alien in others. I had no way of knowing if I was weirder than my application let on, until I started leaking a few of my secret thoughts, first to dear friends, and then to complete strangers. I found out that I was in good company.

Throughout the adoption process, many secret thoughts reveal themselves.

The Adoption Decision

For many would-be parents, the choice to adopt is less of a pro-active decision than it is a resignation to the fact that their bodies won’t do what they want them to. It was exasperation more than enthusiasm that motivated my husband and me to stop being victims of fertility humility.

Once we decided to look into adoption, two things happened. On the positive side, sex was no longer a homework assignment. On the negative side, we weren’t at all sure that we could love someone else’s child.

I started looking closely at kids. I saw toddlers with runny noses, babies with blotchy red scalps, and gruesome looking teenagers. The sayings and songs about the beauty of all children can only be metaphorical. It’s impossible to tune into any kind of inner beauty when a kid is screaming or drooling or calling another angel a “doo-doo head.”

I wondered whether the baby we would adopt might turn out to be a dud–neither charming nor cute. I know looks aren’t everything, but it’s tough to maintain mature behavior under stress. Adoption is like being set up with a blind date with whom you’ll have to spend the next eighteen years.

The Adoption Audition

Would-be adoptive parents want to resemble nothing short of Mr. and Mrs. Perfect: delightful and attractive, down to earth yet financially secure, eager but certainly not desperate. It’s quite a strain to look that good. At least it was for me.

Our house had never been as clean as it was during our homestudy. Not only did we vacuum, dust, and scrub the toilet bowl in the guest bathroom, we bought flowers for the coffee table (not an arrangement, just a casual looking bunch), framed our wedding photo, and put our niece’s drawing of a rainbow up on the fridge with balloon magnets.

I think we were secretly hoping that our social worker would stop the interview and exclaim: “You are much too wonderful to spend another childless night. Let me run out to the car and get you the most beautiful and healthy newborn baby there ever was. And by the way, she’s got your eyes!”

After going through the homestudy process–one of many humbling steps along the grovel train–you may resent the power that your social workers and others have over you. “Some of these gatekeepers couldn’t even pass their own tests,” you might catch yourself thinking. You’re also likely to resent the fact that “normal” people (like most every one of your friends) haven’t had to pass pop quizzes, mid-terms and final exams in order to have a baby.

The Ultimate Job Interview

Those of us who get to meet a birth mother have another hurdle to jump, this one, even higher. You haven’t the foggiest notion of how to act, except that you desperately want to please and want to like this person–a complete stranger and the most important person in your life.

For me, this was the ultimate job interview. The young woman sitting at my side was holding our parental destiny in her hands (well, her uterus). She may have been feeling vulnerable at six-months pregnant and without a boyfriend or health insurance, but she was actually the powerful one. Where once we were supplicants to our forty-year-old bodies, our new fertility goddess was only eighteen.

She needed us, we needed her. We were all part of an unspoken conspiracy to make it work. The adoption process–casting the best light on all parties and putting a premium on the end product-would make a great case study for a marketing textbook. By the time you’ve reached the lawyer’s office and have met a birth mother, you are as close to a baby as you’ve ever been, and you just want to close the deal.

Our match was far fetched by virtue of the differences in skin color, religion, age, and ethnic diversity between birth and adoptive parents, and yet, we felt a connection with our birth mother and, whether real or wished for, a growing sense that this was meant to be.

The Myth of Bliss

On what is supposed to be the happiest day of your life–the day you receive your baby–an adoptive mom can feel very sad. I wanted a baby, but not someone else’s. “I am the one who should be horizontal, not vertical,” I thought. This was not what I pictured motherhood to be.

I know that the baby’s presence in my life means his absence in someone else’s, and I wonder if my birth mom’s baby will ever feel like mine. I was a very sad, dazed new mother. This kid came with so much emotional baggage for me. Adoption is just as bitter as it is sweet. Maybe more.

I was not one of those beaming, brand-new mothers, swelled with pride and blinded by baby love. I knew this was supposed to be the happiest day of my life, and that made me feel even worse.

Separation Anxiety

When our son’s first mother chose to relinquish her baby, he was an “it” and not a “he,” a blob on a sonogram, and not a giggling, brown-eyed beauty. If ever I could understand her decision, it was then, not now. Once she saw him, how did she go through with it? She spent two days with him in her hospital room. How did she know when it was time for a last kiss, a last touch, a last look?

I was so ready to despise our birth mother for changing her mind. But she didn’t, even after holding the baby, even after feeding him. When we were told we could take the baby home, all I could feel was shame for assuming the worst.

What flashed through my mind, however, was far short of grateful: “What’s wrong with this baby?” “Is there something she knows that I don’t?” “How else could she do it?” I thought to myself.

Most adoptive parents live with some anxiety about the birth mother changing her mind. Many adoptive mothers can understand why she would. The grief of adoption is not lost on the woman who brings the baby home.

Belated Bonding

To my dismay at the time, an adoptive mother once told me: “I fell in love the instant I saw the baby; at that moment I knew she was mine.” I’m here to say that instantaneous connection doesn’t happen to everybody. But most of us don’t advertise our delayed passion. I assured myself it’s not normal to adore someone from the moment you meet; most people need to get to know the other person first.

When my son was between nine months and one year, I fell in love with him. It wasn’t until then that my feelings exploded into the fiercest of passions. I know you’re supposed to do it sooner, but it took a little while for my heart to catch up.

Ungrateful Thoughts

Grateful though we should be, adoptive parents are not always. I was anything but grateful one night when my son was two. It had been a three-tantrum day, and there he was in his high chair, throwing spaghetti directly at my face.

I could feel the tomato sauce sinking into my hair and can remember thinking the most horrible thoughts: Who is this kid? Where did he come from? Are we dealing with a bad seed here? If he’s this angry now, wait till he understands that he was adopted, that he doesn’t look a thing like his parents. What will he throw at me then? Would my biological child have flung spaghetti at me? And worse: Can we return him?

Thankfully, you can’t get arrested for your private thoughts (I would have been behind bars long ago). I’ve since learned that loads of new parents–both the adoptive and biological variety–fear that they’ve ruined their lives at some point as their children evolve. Somehow, perhaps because all kids eventually will fall asleep and ultimately will grow up, you sign on for another day. And then another.

The Adoption Excuse

Whenever my son cried as an infant, and I couldn’t figure out what might be causing his grief, I jumped to conclusions that haunt vulnerable adoptive mothers like me. I was afraid that my baby was crying because he missed his real mother and knew that I was only a fake. At a primal level, infants must know colostrum from formula.

One of the primary filters through which adoptive families interpret the world can be labeled in two parts: “adoption-related” or “something else.” It’s not that thoughts of adoption stay in the forefront of an adoptive parent’s mind, but they are never so far away that they can’t be called up in a millisecond. At the slightest hint of an unfamiliar trait, an unaccounted-for quirk, a hard-to-pin-down quality, or an undesirable behavior, comes the question: “Is that adoption, or is that something else?” Like that old commercial: “Is it live, or is it Memorex?”

Many parents hypothesize that Jason picks his nose because he needs attention or wants to defy the rules. Adoptive parents worry whether Jason picks his nose to comfort himself and to assuage his insecurity about being separated from his birth mother. Truth is, Jason may pick his nose because there’s something well worth picking in there.

Two Mothers

Whether or not you’ve met the birth mother of your child, she has a presence in your life. Our paths crossed for the first time six years ago: She had a baby, I had a home. The emotional symbiosis of that solution is not severed with the legal ties. She is forever a part of my son’s life and mine; and he will always be a part of hers.

I am eternally grateful to our son’s birth mother, but wish I had never needed her. We remind one another of the gains and the losses in each of our lives. That makes ours a loaded friendship, a complex connection.

Every time we send pictures to our son’s birth mother, we have a choice: Do we send cute or ugly photographs? Should they be close-ups or full-body shots? Perfectly crisp or acceptably fuzzy? Gleefully happy or just contented? Irresistably adorable or just sweet? A single roll of 36 exposures presents us with at least that many choices.

The real question is, if his birth mother sees how beautiful and compelling her son is, will she want him back? The law says she can’t have him back, the adoption is finalized. But it’s creepy to think that she would if she could.

I need my son’s birth mother to help me paint a complete picture of who he is and where he came from. There are questions only she can answer, commonalities only she can offer. I’d like her to be interested in his life and happy with her own; involved, but not possessed or possessive. I can’t custom order a birth mother any more than I can a baby, but if I could, she’d be like a favorite aunt.

Interracial Complexities

Adoption of a same race child would have been enough of a stretch, but we went one step further, with a baby that came out of someone else’s body and someone else’s culture. When I first met my son, I felt overwhelmed by the responsibility of teaching him things I couldn’t possibly know as a white woman. And I felt sad realizing that we’d never be mistaken for mother and child.

Back in our pre-adoption “Dark Ages,” I thought race was a non-issue when it came to parenting. In fact, it is the issue. We have to deal with race before adoption, because it is more immediately noticeable.

I’ve evolved from an unenlightened white woman who thought all people should be treated equally, to an enlightened one who knows they are not. And the transformation has sharpened me in ways that scare some of my friends. Life is hard enough when you resemble your parents. What have we done by making it harder? What has his birth mother done by choosing adoptive parents of a different race? I can’t figure out if this child should sue us all for negligence or thank us all for our naivete and blind faith.

Conclusion

As the secrecy surrounding adoption diminishes, emotional territory that was once taboo is less so. As more and more of us tell the truth about our feelings, and those feelings resonate with others, they gain a legitimacy that can be comforting.

Like every other aspect of adoption, truth is not a gift that you can choose to give or withhold; it is a prerequisite. The process of adopting a child takes more courage than you think you have, offers more self-knowledge than you think you want, and reassembles your characteristics into someone familiar but changed. It is an incredible journey through a rich landscape of hard truths.