Eight years ago, I became the mother of a 26-year-old man—a virtual stranger with whom I had little in common other than a handful of genes, and no history beyond the nine months he had spent in my belly.

Like many birth mothers, I had no more children after relinquishing my baby, in 1970. My sole experience with parenting came when I married 12 years later and became stepmother to my husband’s 16-year-old son. I failed miserably, although I can’t take all the blame. Being dropped smack into the middle of his troubled adolescence, I probably didn’t have much of a shot. My tendency to replicate my own parents’ rigid style (which I had hated, growing up) didn’t help. Twenty years down the road, my stepson and I have a wonderful relationship. But our first few years together—coupled with guilt for having given up my only child for adoption—left me certain that I was not “mother material.”

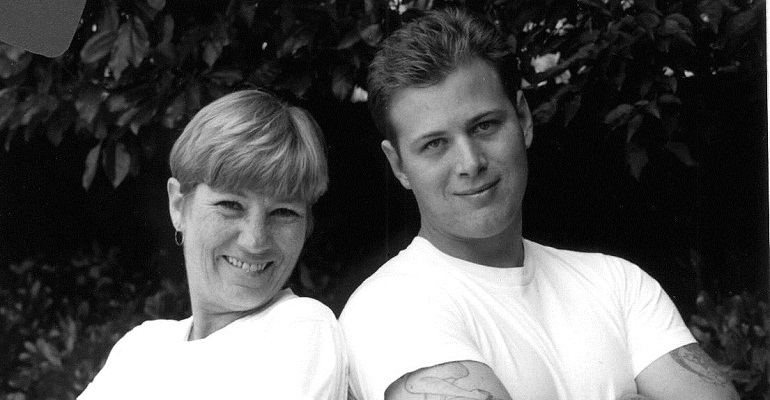

When my birth son and I found each other, everything changed.

Contrary to everyone’s assurances that I would “forget and move on”—conventional wisdom at the time I relinquished my son—not a day went by that I didn’t think of him. Although I was afraid to search, I registered with International Soundex Reunion Registry when he turned 18. An ISRR search is by mutual consent (both parties must file for a match to be made). After eight years with no results, I had given up hope. Then the call came. My son had registered two weeks earlier. We talked that night, and 10 days later I was on a plane from San Francisco to New Orleans to meet him.

My Adult Child

From the beginning, Josh called me “Mom” and said he loved me. As he described his difficult childhood and teen years, his failed first marriage, and scrapes with the law, I was overcome with guilt for having left him. And I wanted to make it up to him. He and his second wife, an equally troubled 17-year-old who was expecting their first child, were financially and emotionally needy. He was estranged from his adoptive parents—so much so, that we didn’t know until later that his adoptive mom had died a month before. He was clearly looking for a mother, and I desperately wanted the job.

Most adults—adopted or not—don’t need, let alone want, parenting. And most adoptees, when they decide to search, aren’t seeking another mother. In reunion, there are issues to address, feelings to process, and expectations to resolve. Even in her relief and joy at finding her child, the birth mother often feels unexpressed grief, shame, and guilt. The adoptee may feel angry, overwhelmed, or disloyal to his adoptive family. But once the dust settles, the birth mother and her son or daughter are essentially two grown people with their own lives—which can include each other on a healthy, adult level.

I didn’t know that in 1996, and I didn’t care. For the first time, I felt lucky, fearless, and worthy of motherhood. My long-buried maternal instincts surfaced in an euphoric rush, and I leaped whole-heartedly into the relationship. Our first year was a “honeymoon,” enhanced by our easy relationship, cross-country visits, and the birth of my granddaughter.

When I look back, I see that Josh and I acted out the natural stages of parent and child at an accelerated pace. After months of enjoying his childlike behavior—the cute magnets he sent me, and his inability to make even the smallest decision without my advice—I began to resent the level of attention he needed. But by then, he had changed into a demanding, defiant teenager. His expectations of what a mother should be, and my inability to meet them, crashed head-on.

At first, I ignored his history and believed that he would be fine once he had me in his life. The longer I knew him, the more worrisome his problems became—his inability to maintain relationships, lack of compassion for others, and quick temper. I watched helplessly as his second marriage disintegrated. When his wife left him and their 10-month-old daughter, he turned to me. I was willing to help until it became clear that he held me responsible for his misfortune and expected me to change my life to repair his.

The next few years brought more confrontation. He jumped in and out of jobs, married and divorced again, and moved around the country, sometimes without telling me where he was. Trapped between my own need and fear of losing him—possibly forever—it was all I could do to hang on.

Changing Me

It took a long time to grasp that I was not doing him any favors by trying to rescue him or to compensate for what was long past. I had to learn to set and maintain boundaries. I had to resist the urge to “fix” him and solve all of his problems (which may or may not have come from being relinquished, and, boy, did I suffer guilt with that one). I had to accept him as the person he was. I had to stand up to his tests—so obviously aimed at seeing if I would leave him again—and trust that our relationship would endure. I had to demonstrate healthy adult behavior and respond to him with love, even when I didn’t like him very much.

Parents, both biological and adoptive, learn such lessons every day, often through trial and error—although usually with the advantage of having started at the beginning. They have plenty of role models, while birth mothers do not. We are an invisible lot and rarely have the benefit of one another’s insight until we are distraught enough to seek support. Friends and family members who have raised children, while well-meaning, come from a different experience. With openness and reunion on the rise, there are now more resources: books, support groups, and therapists who are knowledgeable about relinquishment, adoption, and reunion. I used these to learn to be a good mother. It was a long-term project, like raising kids.

Making the necessary changes in myself was hard work, and the changes often met with resistance from Josh. Over time, our battles became less terrifying, our “time outs” less devastating, and things began to improve.

Something else happened along the way: Josh hit his thirties. He matured and settled. Although it’s impossible to know for sure, I like to think that my presence in his life played a part. So did his fourth (and, I hope, his last) wife, who also refused to give up on him. They’ve been married for five years and, between his, hers, and theirs, have four children.

Josh and I have had our ups and downs, but I’m pleased to say that today we’re on a steadier track. We still disagree—about money, manners, child-rearing—and we probably always will. But like most parents with grown children, I can now relax a little and enjoy being a mother and grandmother. I’m pretty good at it, after all.