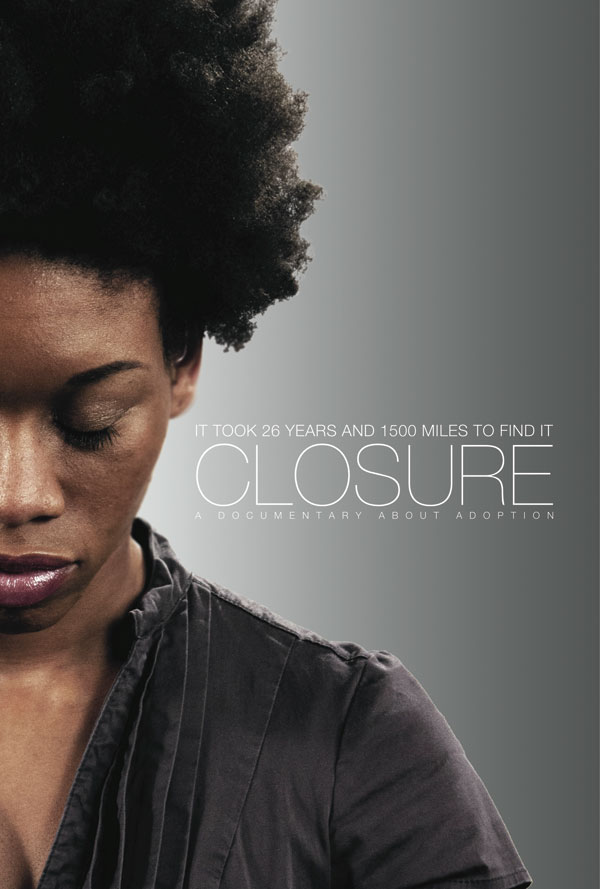

Who is my birth mother? My birth father? Was I abandoned at the hospital? What would it have been like to grow up with them? With parents who were not White? Angela Tucker, adopted from foster care at one year of age by a family with eight children, in Washington State, grew up dwelling on these and other questions about her origins. When she was 26, she set out to find the answers. Her husband, Bryan, captured the search, and the many reunions that followed, in the documentary feature Closure. Both subject and filmmaker are quick to remind us, “This is just one story,” but it is an undeniably powerful one that has spoken to thousands across the country.

Adoption at the Movies‘ Addison Cooper spoke with the Tuckers about explaining Angela’s need to search to her family — and their eventual understanding, the initial rejection she received from her birth mother, the invalidating effects of “color blindness,” and the special connection her moms have developed.

Angela, you’ve said that the desire to meet your birth family has always been in you. What were the feelings like as a kid, and how did you decide to begin your actual search?

ANGELA: I’m a pretty inquisitive, curious person by nature. I was always teased by the idea that I could have access to my original birth certificate when I was 21. I tried to get that, and was not successful. That inspired me to use other methods to search.

You’ve said that your family didn’t recognize your deep need to find your birth family, and, in the film, they shared some of those feelings and worries. How did your family come to understand?

ANGELA: I think my family’s outlook was similar to that of many adoptive families, in that they recognized my need for a birth family search in the context of some safer topics, like learning my medical history or obtaining my original birth certificate — but they didn’t understand the emotional component of my need to search. But I truly felt a need to see my birth family and foster family, to learn the circumstances around my placement. And, when these moments actually happened, I felt a lot of relief.

Although some of my reasons for searching were difficult to verbalize, my family began to understand and appreciate it. My mom said that she put herself in my shoes at a certain point during the search, and realized that she would want to know these things too.

|

| Angela and her mother, Teresa, on their first phone call with Angela’s birth mother, Deborah. |

Sometimes you hear people talk about someone who was adopted and “never wanted to know” about her birth family or “never felt a need” to search — with the implication that that’s ideal or exemplary.

ANGELA: That’s a multifaceted statement. If an adoptee says that, it could be rooted in her generalized fear around learning her own story, or she could be trying to appease her adoptive family — or a number of other reasons. If the adoptive parents say, “That’s one person’s story, but I wonder what you want,” that opens the door for the adoptee to share her feelings.

When you went to find your birth family for the first time, you went with your whole family.

ANGELA: I’m so glad I did. I don’t know how I would have done it without them. It would have been really scary to do it alone. I hear adoptive families say, “We’ll let them find their birth family some day, on their own,” but that sounds dismissive. I’m grateful to have had a safety net.

|

| (left to right) Deborah, Na-Na, Angela, Elena, and Teresa, shortly after their first meeting in July, 2011. |

What was it like to meet your birth parents?

ANGELA: I went to my birth father’s home first. I remember seeing my birth father’s last name on the callbox. A woman answered the door and I immediately noticed that we have exactly the same skin tone. I’ve never seen anyone whose skin tone matched mine so closely. I explained who I was and what I was looking for, and she confirmed that my birth father was her son. I was very excited. My birth father passed by on his bike, so we flagged him down to talk with him, and noticed that we looked exactly alike. It was very powerful, as I had wanted to see someone whom I physically resembled for so long.

Sometimes, adopting parents proudly talk about being “color blind” — but for Angela, seeing the physical connection seemed pretty powerful. What do you both think of the notion of color blindness?

BRYAN: There are two facets of color blindness — being open to adopting a child of any race, and choosing not to incorporate racial issues. In that second respect, color blindness doesn’t seem healthy. It’s important to make a child feel comfortable with his skin color, heritage, and history.

ANGELA: When adoptive parents say that they’re color blind, I feel that they’re trying to lessen the distance between the child and themselves, which makes sense in the familial context. For example, I don’t notice Bryan’s skin color on a daily basis — it’s not important for me to see him as White every night when we get home, but this doesn’t mean I am ignorant to what it means to be married to a White male. But it can also sound like they’re stating that they don’t know, don’t see, and don’t care to know how and why people of color experience microagressions and racism still today. I think a more helpful statement would be: “We are family first, regardless of color or genetics. But I see your race and I am attempting to learn what it means to be a person of color in today’s society.”

For a lot of adoptees, one big fear is that they’ll search, find the relative, and then be rejected. You initially experienced that with your birth mother. How did you recover enough to give her a second try?

ANGELA: There is pain in being rejected, but I have some empathy for her reaction. I knew that I have birth siblings and birth aunts and birth uncles who might want to know me, so I shifted my focus to them.

|

| Deborah and Angela on the Tuckers’ last day in Chattanooga, July 2011. |

There was a lot of acceptance from your birth father’s family. How has it been for your family, accepting both sides of your birth family?

ANGELA: They really love them all. My mom absolutely loves my birth mom, Deborah. She feels so connected to her. They are as different as different can be, but both of them feel that connection to each other. My birth mom and mom correspond weekly, at least, via email. It’s a really healthy, respectful relationship.

How much contact do you have with your birth mother? With other family members?

ANGELA: My birth mom recently got the capability to do Skype! We were able to Skype together for the first time this weekend. I’m in touch with my birth father’s family by text and Facebook. They are all so proud and have fully embraced me as their “new niece” and Bryan as their nephew. My birth sister texts me pictures of her kids, which I love, because she wants me to be an active figure in their lives. An aunt keeps me updated with everyone’s health and with changes in their family. It’s fun, although the geographical distance and difference in time zones makes communication a bit harder.

What feedback have you received about the film?

ANGELA: Adoptive parents report a sense of better understanding how to support their child in general, not just in the actual search. Birth parents also feel that it shows the hidden wound of relinquishing a child, and view Deborah, with her vulnerability, as someone to look up to. It helps that the film has no agenda.

BRYAN: The feedback that we’ve received from adoptive parents has been mostly positive. They look at Angela and other people in the story, and relate them to different people in their own stories. There’s a danger that people could watch this film and think that we’re saying that this is how the experience of search and reunion should go, or that this is the way transracial adoption should be represented. But it’s just one story, told by several voices. It takes more people sharing their stories to inform the public about all the ways reunion searches can go.

People say that the film is not giving them answers, but it is helping them ask questions about their own adoption journey or the journey of a loved one. I hope it continues to get into the hands of people who are touched by adoption, and people interested in adoption.

|

| Angela watches as Teresa shares a scrapbook of Angela’s life with Deborah. |

What message or lesson do you think adoptees might take from your story?

ANGELA: I hope that it can start to normalize the feelings adoptees have — that we can search and have love for birth parents and love our families at the same time. I’m interested in phasing out the “cover” of adoptees needing to justify their search as seeking medical information. I want wanting to make a connection, to get answers, to be OK as a primary reason. I want them to feel empowered to do that. For adoptive families, I hope they can see that supporting adoptees in this can be powerful for their relationship. One family certainly does not replace the other.

Stream Closure or buy it on DVD at closuredocumentary.com.