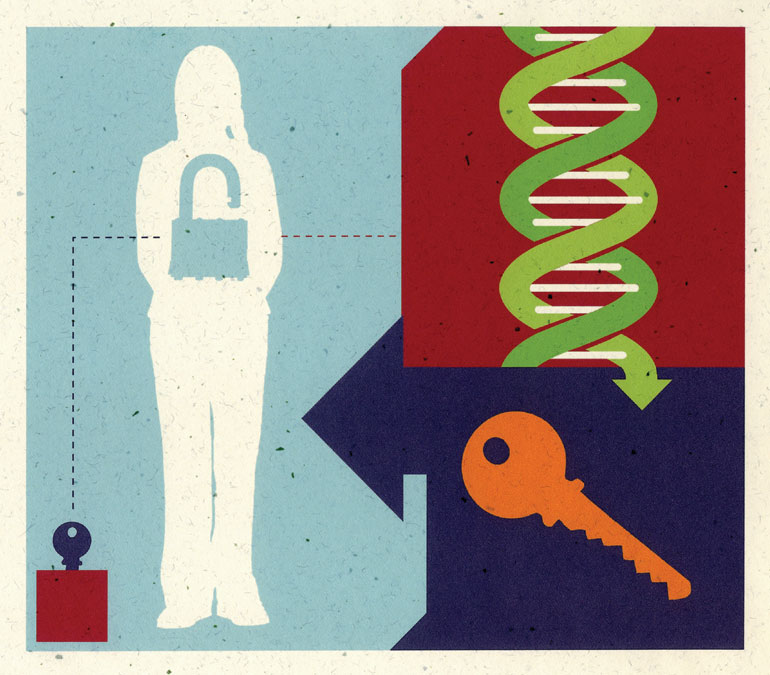

If you watch CSI or read the newspaper, you know that DNA testing is used to nail the bad guy or to free a wrongly convicted innocent, sometimes years after the crime. But you may not know that it’s also being used, with increasing frequency, in adoption.

In the search for a biological relative or to trace a child’s ethnic heritage, the human genome can provide critical clues that are unavailable in medical or orphanage records. But genetic testing, still in its infancy, can be inconclusive. Here, Adoptive Families looks at several ways our families are entering the high-tech world of DNA.

Searching for siblings

Most of our kids have biological siblings out there somewhere, whether they are known or unknown, living with birth parents, or adopted by another family. And finding a sibling is, without question, one of the greatest joys for adoptees and their families.

Five years ago, Amy Klatzkin, of San Francisco, received a letter from an adoptive mom in Europe. She’d seen a picture of Klatzkin’s daughter on the back cover of the girl’s adoption memoir, Kids Like Me in China (Yeong & Yeong), and sent Klatzkin photos of her own daughter, also adopted from China — and a dead-ringer for Klatzin’s.

Klatzkin was fascinated by the close resemblance between the girls, then eight and 10 years old, and shared the news with her daughter immediately — something she now regrets. The girls were so excited by the prospect of being biological sisters that Klatzkin found herself swept up in their enthusiasm. She began, along with the European family, to investigate.

Most labs she called said the technology wasn’t advanced enough to prove siblingship without a sample from at least one birth parent. The two “sisters” from China, like many adopted children, had no way of obtaining this key piece of the puzzle. But the moms kept searching until they found a lab that agreed to perform the DNA test.

Before sending in the girls’ cheek swabs, the families met in Europe. The girls’ looks, as well as their mannerisms, were “eerily alike.” “They just stared and stared at each other. It was incredible to them,” says Klatzkin. But, just weeks later, the girls’ giddy enthusiasm was deflated. The test results were inconclusive.

Why is a sibling match so hard to pin down? Because every person inherits half his DNA from his mother and half from his father. Theoretically, siblings would share at least 50 percent of the same genes, says JoAnn Boughman, Ph.D., executive director of the American Society of Human Genetics.

But because these tests are only looking at a tiny fraction of the genome, there’s always a chance that a sibling relationship will be missed. False positives also happen; concentrations of certain genes that develop in isolated populations, such as in rural China, may lead to unrelated children appearing to share identical strands of DNA.

As the testing geneticist explained to Klatzkin, results of sibling tests performed without a parental sample can never be 100 percent conclusive, except when the children tested are identical twins.

Twinship testing

Angela Powell, from Oklahoma City, adopted 17-month-old twins, Alex and Gabriel, from the Ukraine. She wasn’t told whether they were fraternal or identical, but noticed that they both have hypothyroidism, hit major milestones at the same times, and looked like mirror images of each other. Powell decided that it might be useful to verify her sons’ relationship for medical reasons.

An ad in Twins Magazine for Proactive Genetics caught her eye. In 2005, she contacted the company about DNA testing, and her hunch proved right: Alex and Gabriel are identical twins. Last year, Alex was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome, a disorder on the autism spectrum that is typically genetic. Surprisingly, Gabriel tested negative for Asperger’s.

The fact that the boys were identical twins helped their doctors confirm that Alex’s condition was neurological (most likely caused by trauma at or soon after delivery), rather than genetic in origin. Not only was this information helpful for determining his treatment, it also told the Powells that it’s unlikely the boys would pass the disorder along to their biological children.

Choose your lab wisely

Angela Powell’s story is not typical, however. More common are the stories of adoptive parents like Klatzkin, with nothing more than a snapshot and a belief that her child bears a striking resemblance to another. Klatzkin and her daughter received no counseling before deciding on the test, and she wishes they’d been better prepared for possible disappointment.

Today, there are hundreds of labs willing to do sibling tests (usually for a fee of several hundred dollars), despite the limitations. And since for-profit labs are doing the work, rather than universities or medical institutes, Klatzkin doubts that counseling will become a routine part of testing anytime soon.

To prepare yourself for such a test, Dr. Boughman recommends finding a lab whose claims are “completely transparent”; in sibling testing, this means admitting up front that there’s a slim chance the result will be conclusive.

Although no regulatory body governs DNA labs, the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments program (CLIA) monitors quality control and publishes a list of labs that have had their licenses suspended.

Instead of doing case-by-case testing, some adoptive parents have formed DNA banks, such as Kinsearch or China DNA Project, to match biological siblings from a large pool of samples. Such groups offer support through the process, but be sure to sign up for one that contracts with CLIA-certified labs.

Klatzkin’s family eventually found a resolution. A Chinese-American uncle explained to Klatzkin’s daughter that, in Chinese culture, if you feel in your heart that someone is your brother or your sister, you are siblings — regardless of a blood relation. Klatzkin says this idea helped her daughter learn how to value the friendship she’d begun with her “sister” in Europe.

Analyzing ancestry

Some parents aren’t looking for siblings, but want to learn more about their children’s backgrounds. An important part of adoptive parenting is instilling our children with pride in their roots, but when your child’s ethnic makeup isn’t obvious, it can be hard to know which festivals to celebrate or picture books to read.

Ethnicity can also predict a predisposition to certain diseases or genetic disorders. And knowing something concrete about his background is helpful to any child going through the identity crucible of the teen years.

Carita Zimmerman and her husband adopted their daughter, Fiona, as a newborn. Although they continue to see Fiona’s birth mother, a Caucasian teenager, she has not been forthcoming about the birth father. Fifteen-month-old Fiona has light tan skin, but is of no obvious ethnicity, so the Zimmermans have decided to pursue ancestry testing.

Ancestry testing also has its caveats. Every human being is essentially an “admixture.” If any of us traced back 20 generations, he’d be looking at a million ancestors. And because, essentially, genes are passed on at random, it’s nearly impossible to predict the combination of traits that will be expressed in a particular child, says Lou Charlton, Ph.D., of DNAPrint Genomics.

And just as sibling tests for adoptees are more conclusive if parental DNA is factored in, ancestry labs recommend backing up testing with the kind of paper records — letters, old photo albums, family trees — that adoptees rarely have access to.

The Zimmermans hope that Fiona’s birth mother will change her mind about talking about the birth father as Fiona gets older. Although they’ve contacted a company in Seattle called Genelex, they have decided not to test until Fiona is old enough to start asking questions.

When choosing a lab, parents should check to see if the lab works with reputable institutions; for example, DNAPrint works with both Harvard and Penn State universities. Zimmerman felt comfortable with the American Association of Blood Banks certification cited on Genelex’s website.

Steer clear of labs that claim the ability to pinpoint ancestry by country (e.g. saying a child’s ancestor’s came from Poland or Germany). Border changes and immigration patterns make it virtually impossible to determine ancestry to that degree.

Pre-adoption DNA testing

Guatemala is currently unique among sending countries in requiring DNA testing to guarantee the biological relationship between a relinquishing birth mother and the potential adoptee. Such testing affords adoptive parents great peace of mind.

“Knowing that the woman relinquishing our daughter is, in fact, her birth mother is reassuring to us,” says Karen Kloss, who is eagerly waiting for the green light to travel to Guatemala to adopt a baby girl. Kloss says she “would be horrified to find out, years down the road, that her child’s birth mother did not actually plan on and place her for adoption.”

For other families, receiving DNA test results and a photo has helped them establish direct contact with their children’s birth mothers in Guatemala, leading to something of an open adoption trend.

Sandra Handwerk, who adopted biological brothers, met the boys’ birth mother on her adoption trips, and sends photos to her every Christmas. Kloss, who is planning to meet her daughter’s birth mother on her trip to that country, anticipates “keeping in touch with her way into the future.”

Identifying birth parents

South Korea has the oldest international adoption program, and, as its adoptees enter adulthood, many have embarked upon birth family searches. Because South Korea is thought of as a bellwether of what’s coming in international adoption, more searches may lie ahead for international adoptees as they come of age.

Commenting on the apparent lack of birth parent information for children adopted from China, Hollee McGinnis, a Korean adoptee and founder of the adult adoptee organization Also Known As, points out, “[Korean adoptees] came from the same situation — we were left at police stations, we thought there was no information. And, lo and behold, reunions are happening.” McGinnis found her own birth parents in South Korea when she was 24.

When available, South Korea’s adoption records are generally detailed, but the paper trail doesn’t always lead to a match. When this is the case, some adoptees take their search into the public domain, posting ads in newspapers or appearing on television with any birth parent information they have. Usually, the only way to prove whether anyone who comes forward is the adoptee’s biological father or mother is by DNA testing.

In her poignant 1998 documentary, Crossing Chasms, adoptee Jennifer Arndt describes her extensive search for her birth mother in South Korea. A DNA test proved that the woman who seemed to be her birth mother was, in fact, not. Recently, the skier Toby Dawson publicized his search for his Korean birth family after winning a bronze medal at the 2006 Winter Olympics.

DNA testing has, so far, ruled out all the men claiming to be his birth father. Still, Susan Soon-keum Cox, vice president of the adoption agency Holt International and a Korean adoptee who found her birth parents at age 39, points out the benefit of such testing, whether it identifies a birth parent or rules one out: “In any sort of public search situation, the adoptee and all the potential birth parents who come forward are so excited, and want this so much, that it would be hard to remain objective without a DNA test.”

As more adult adoptees pursue DNA testing to find their birth families, McGinnis reminds us, “A genetic connection doesn’t necessarily make a relationship.” In other words, we shouldn’t lose sight of what adoption taught us in the first place: Families are made of people who love one another. They don’t have to be built through biology.