Mary Ann, the head nurse at the clinic, comes in to tell me that the patient in the next room is Athena Harris. It’s not really Mary Ann’s job to tell me this; it’s my job to grab the next chart and walk into the next room and deal with whomever. But Mary Ann is announcing Athena, our old friend, and warning me that whatever’s going on in there, it’s likely to take me a while. Mary Ann makes a baby-cradling gesture across her chest.

“You’re kidding! Don’t tell me!” I say in shock and horror, but we can both hear that I am also saying, Good old Athena, here she goes again.

And sure enough, there is a tiny, brand-new baby in Athena’s arms when I walk into the room, and she smiles at me with proud possession, the way a new mother not on her first baby might smile at the doctor, an experienced mom who wasn’t overwhelmed with fear, because she’d been this route before, but who wanted some acknowledgement that each new baby is a miracle and a joy.

Except maybe when all your other children have been removed from your custody, of course.

“‘Lo there, Dr. Lucy,” she says. “Look what I got.”

“I didn’t even know you were pregnant, Athena,” I say, and she smiles again, as if she has once more pulled off a special trick.

Athena is not from Boston. She’s from somewhere south, and, because she is southern and white, a category that is not particularly well-represented in our Boston clinic, any number of people have described Athena’s social category as “trash.” We allow ourselves, I suppose, to be a little freer with the slurs when a person is white.

“It’s a little girl again this time. Popped right out. One more week and she could have been a Thanksgiving baby.”

There is a much-too-big snowsuit lying discarded on the exam table — but at least there is a snowsuit. I peel back the edge of the receiving blanket, which I note without surprise is hospital issue, and stare down at the round, pale face. Eyes closed, eyelids even paler than the rest of her, papery crescents that tremble slightly as she sleeps as if the blood pulsing through her small body was almost too much for her. The baby has a halo of bushy brown newborn hair.

“She’s beautiful, Athena.” I tuck the blanket back around her and take my own seat across the little desk. “How many is this now?” I ask, trying to keep my voice light.

“This here’s number ten,” Athena says proudly, drawing out the word number into two drum-roll syllables, as if she were announcing a record broken, a winning lottery combination, a grand prize. As if numbers one through nine were not in the various stages of temporary placement, long-term foster care, termination of parental rights, and adoption.

“Number ten,” I repeat, without special emphasis, I hope.

Athena was probably beautiful once, though since I have known her, which is a good seven years, she has always had that used-up look. In between children she diets down and takes on a hungry, rangy look, all tight jeans and tank tops.

Today, postpartum, she is soft-edged again and wearing black stretch pants and a faded long-sleeved shirt, printed on the front with a picture of a swan boat. It’s the kind of shirt she might well have gotten from the clothes pantry downstairs, since surely Athena’s children have never been taken on a swan boat ride, at least not by Athena. Although as I sit here in this fluorescent-lit room on this dark November day, suddenly I can picture it: summer in the city a couple of years ago, one of those heavily funded family preservation programs, some very well-meaning social worker leading Athena and any three or four of her children through the Public Garden, eager to give them this strong, positive family experience. They wait in line, and the social worker buys them all bags of peanuts to feed the ducks.

The children are wild with excitement on the ride. Pointing out the ducks coming to follow the great white swan boats, tossing peanuts wildly, and squealing as the ducks dive or chase each other off. Blinking and looking around at the green banks of the Public Garden, the blue sky above, the families sitting under the trees and waving to them. And the quick looks you get at the city around you in all its glory, the Ritz-Carlton over there, and the pleasantly distant mutters and putts of traffic on Beacon Street. What city is this? The children are wondering. Who made this magic? Can this be Boston?

*****

I examine Athena’s new baby. Perfect in every way. Perfect except for being born into a situation you wouldn’t wish on a jellyfish or a dung beetle. I refasten the diaper, re-wrap the blanket, and hand the infant back to Athena.

“What does DSS say?”

“Oh, they filed right away when she was born.” Athena is long past any hostility or embarrassment at the Department of Social Services’ involvement in her life. She speaks of them with a certain resignation, as if she is describing some naturally occurring phenomenon, occasionally inconvenient in its eruptions, like an attack of cold sores. “So after they filed, what’s the situation? I mean, they let you take the baby home?”

“They got an open case on me,” she says, as if her case had ever been closed. “Say I can keep her if my urine checks every two days and I go to appointments and you say she’s okay. Got a visiting nurse coming every day to weigh her on one of them portable scales, and got a home visitor comes and passes the time of day. And my caseworker, of course. She’s the one who brought me here today. She’s out in the waiting room.”

And what are the odds, Athena, that you’re going to keep her past her first birthday? Even with the visiting nurse, and the home visitor, and the caseworker? Will you two even make it through the winter together?

When I was ten years old, I read Oliver Twist. I was a foster child, and actually, I was given the book by the woman who would take me in and then adopt me, the woman who would determine the course of my life. I was a good reader, but it seemed to me that Oliver Twist was the first real book I had ever read. I read over and over the opening chapters — the poorhouse, the gruel, the beatings! And yet I was well-fed and unbeaten, in the care of respectable New Jersey housewives. When I’ve looked at the book over the past few years, I have been struck by how excellently Dickens made the case for the contradiction that is at the heart of my own life and work. There has to be a system; there has to be a place to catch the people who go tumbling or drifting out of safe society. A net, we would call it today. But here’s the contradiction: the system is not enough; the net does not represent real safety. Institutions and official involvement are not sufficient — but they are necessary.

Athena and I both know, I suppose, that I could send it either way. I could tell her that the baby is healthy, which she seems to be. I could tell her I’ll see her in a week; to the list of Athena’s check-ins and rituals, we will now add a weekly schlep into my clinic for me to weigh the baby and check for any evidence of neglect. Athena will have to feed her, so that she gains weight, and change her regularly, so that she doesn’t develop terrible diaper rashes, and mark her appointments on the calendar. I could end the visit now like any standard newborn visit: Congratulations, your new baby is perfect, get some rest, enjoy her, see you next time. Or alternatively, I suppose, I could go back over as much of Athena’s history as we are able to resurrect, review her every false step and risk factor, emphasize to her the importance of keeping strictly to all the standards that have been set, and remind her, as if a woman on her tenth child needs to be reminded, of the danger that hangs over her.

We sit in the exam room, two women, one baby. I am not sure whether she is waiting for me to say something or whether I am waiting for her.

“Athena,” I say, finally, “do you want to keep this baby?”

“Sure I do, Dr. Lucy,” she says, in a slightly too-eager voice, as if, I cannot help feeling, she is reassuring me, gentling me, letting me down easy.

I am looking at her face, trying to see a sign of that rapturous, overpowering love that makes new mothers offer up anxious promises of care and attention and protection, and I don’t see it, but I maybe see something better, or more convincing, or more touching: a kind of businesslike, experienced-mom acceptance of this new assignment.

“They take her away, you know, if you do a single thing wrong, with your record. Any bad urine test. Any urine test you fake or switch.” Yup, that was Athena, a couple of years ago. Brought a bottle of someone else’s pee with her to the doctor, tucked inside the baby’s diaper bag.

I’m launched now, and I can’t seem to stop myself. “If you miss bringing her in to see me, Athena, I’ll have to let them know. Or if she doesn’t gain weight. You have to watch your every step, you have to do this perfectly. I’m not kidding.”

My voice has started to sound shrill in my own ears, and I stop, abruptly. What am I doing? Athena knows these things as well as I do. She is not my friend; I have helped remove at least three other children from her care, joining forces with the social workers to agree that they are not being cared for appropriately, that they show evidence of medical neglect or nutritional neglect or just plain ignore-them-all-day-long neglect. And now I am sitting here with Athena, telling her essentially all the reasons that she is going to lose this brand-new, tiny girl somewhere along the way.

“Get some rest,” I say at last. “The baby is perfect. I want to see her in a week.”

Athena nods. “In a week,” she says. “Thank you, Dr. Lucy.”

She stands up, folding the hospital blanket more closely around the baby, and then zips the whole bundle, baby and blanket and all, into that too-large snowsuit. She gathers up her purse and the Healthy Happy Families bag that I know the home visitor brought her.

“What’s her name?” I ask, standing aside to let her through the door.

“Cassiopeia,” she answers. “Like in the stars.”

I watch them go out the door, and I think of Athena and her children on that swan boat ride I invented for them. They do not live in that picture-book city, not Athena, not the children who are already gone from her care, not the new baby.

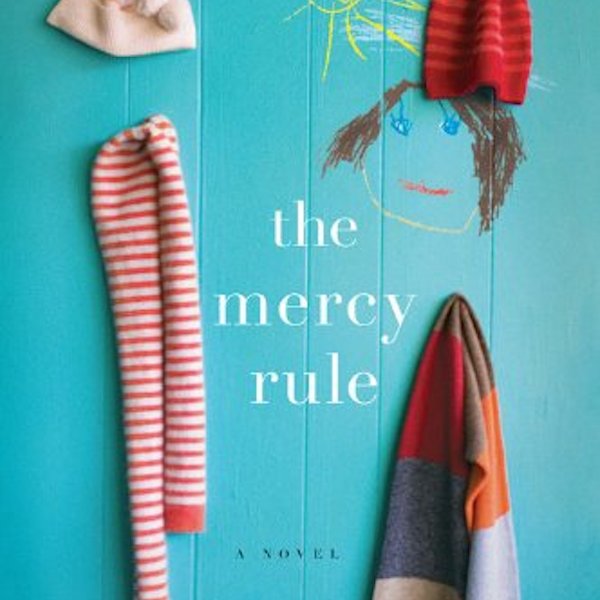

Excerpted from The Mercy Rule, copyright 2008. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.