My eight-year-old granddaughter (“J”) sat beside me on the commuter train as we headed into the city for a day of exploration. We were chatting when, out of the blue, she asked, “Are you my mom’s REAL mother?”

I adopted her mom as an infant. I used to hate the term “real mother.” By the time I became a grandparent, however, the phrase had lost its sting. While “real mom” was a worn-out term to me, I recognized it as a new thought to her.

It was mental scramble time. I eliminated a simple “Yes.” J was eight; at that age, the prefrontal cortex—that area of the brain behind the forehead that allows one to put information in context—is rapidly developing. She was not asking if I was literally her grandma; she already knew that answer. She was asking about the validity of a family joined by love and court documents rather than biology. Ours was an open adoption. J knew some of her mom’s birth family, as well as my and my spouse’s extended families. Some of the birth relatives actively claimed her as “family.” I sometimes referred to them as the in-laws her mom brought into our family. J was struggling to articulate a definition of family within the context of her situation. A simple “yes” from me would stop the conversation, would imply that I didn’t find her question worth further consideration or want to be included in her puzzling.

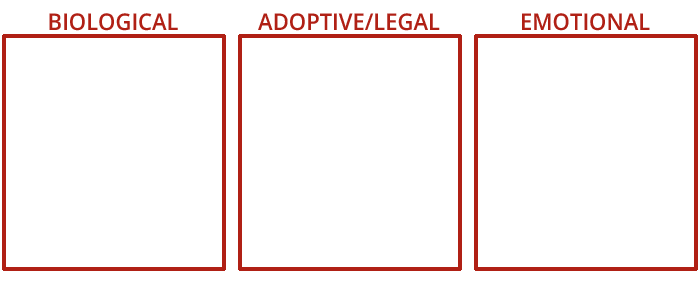

J has always been a visual thinker, so I outlined three imaginary rectangles in the air. I pointed to the first and said it was labeled “BIOLOGICAL.”

“Who goes into this bin besides your mom?” I asked. She named both of her sisters—the one with whom she lives, but also her mother’s first child, who was adopted by another family; her biological father, despite his absence from her life since her infancy; and a few other known members of her mother’s birth family.

“Does that single box fit your entire ‘family’?” I asked. My granddaughter noted that neither I nor Grandpa fit in this bin. Nor did her beloved uncle (my son through adoption), his wife, or their baby.

I re-outlined the second rectangle and said it was labeled “ADOPTIVE/LEGAL.”

“Who goes into this bin?” I asked. Grandpa and I qualify for this “family,” along with her uncle, aunt, and baby cousin, both great-grandparents (one living; one recently deceased), my and my husband’s siblings and their kids, and so on. (Note—her dog made it into this bin, because her family legally adopted him from our local animal shelter.)

“Does this bin cover your entire ‘family’?” I asked again. This bin excluded her oldest sister’s adoptive family, so J didn’t find the second fully satisfactory, either.

I gestured toward the third rectangle, and said, “Let’s label this one ‘EMOTIONAL.’ This is the bin for your emotional family. These are the people you claim. People who love you, now and for the foreseeable future. Let’s start by putting your closest emotional family members at the top. Who would you put in this bin?”

In went her mom, both sisters, grandparents, uncles, aunts, the baby cousin, and some, but not all, of my and my spouse’s siblings and kids. Also omitted were her absent father and his family system. The dog, of course, was included. But so too were several of our longstanding friends who function as emotional aunts and uncles in a more immediate way than several of the legal ones.

“This is the most important bin,” I opined. “This is the one where you get to choose how you define your family.”

“Each of these family systems may hold a different place in your life, but all of them are REAL.”

“OK,” she said, and, as is typical with eight-year-olds, we moved on to discuss something totally unrelated.

J is 11 years old now. As I wrote this, I asked her what she remembers of the above conversation. She remembers the outing, but not the conversation. Then I asked her who she considers her REAL family. She explained that there are several ways to look at family, and proceeded to articulate the categories described above. I asked how she figured all that out. She said, “I always knew.”

My son and several other adopted adults I know are fond of saying, “If you can remember when you were told about adoption, you were told too late.” I am delighted that J has “always known” about her three real families.

POSTSCRIPT: Since having this conversation, I’ve used this concept in my therapy practice. When meeting for the first or second time with an adult, teen, or tween adopted client, I lay out a big piece of paper and explain that, “I think you have three families.” (“Four families” if they lived with foster families or are married with a family of their own creation.) As an opening line, this catches most clients’ attention. I draw and label three (or four) big rectangles. Then we work through a discussion similar to the one I had with my granddaughter. Working through the list of families and identifying which people fit in which boxes helps establish a common vocabulary and clinical norms—e.g., I will honor all the people who shape my client. Curiosity about one’s birth family will not be considered pathology or disloyalty to one’s adoptive family. Noting difference in race, ethnicity, orientation, or skill sets will be welcomed topics for conversation. The very format begs discussion of the gains and losses in adoption, of the presence or absence of important people in their life, and of the availability or lack of availability of predictive information, such as tall you are going to be, what you are likely to be good at, what physical or mental health challenges are worth monitoring closely. I am probably most interested in what kind of support my client has from emotional family as he or she figures out identity, auditions for a school play or sports team, grapples with mental health or academic challenges, initiates a search, develops friendships, struggles with substance use, interviews for a job, chooses a partner, or otherwise moves forward through life. The client whom I consider most at risk is the one with virtually no one in his or her emotional family box.