Make the trip, you won’t be sorry. On a journey last summer to Peru to revisit our son’s homeland, I was struck by the depth of the experience. Weeks after returning, the sights, smells, and sounds of the trip were still fresh.

We made our trip to Peru when my son, Gabriel, was 12, and my daughter, Isabel, adopted from Guatemala, was 9. Traveling with a group of adoptive families, my husband and I looked forward to experiencing the country without the worries that characterized our adoption trip. The group was led by a trip coordinator, and there were guides in each locale. There was a social worker, too, an empathic companion who ran groups for youngsters and adults.

It was exhilarating to be with others whose families had been formed like ours. The usual questions—How long did your adoption take? How long did you live in Peru?—set off animated conversations and created instant bonds. We talked about our child’s readiness to see his birth family, foster parents, or facilitators, while the kids formed friendships over mp3 players and games of tag.

We planned to visit Gabriel’s foster mother, but that would come at the end. First we would savor this country of incredible contrasts, traveling from sea level into the hills, and higher still into the snow-covered Andes. Lima, bordering the Pacific, was as noisy and polluted as the last time we were there, a paradox of European-style restaurants and third-world poverty. But there are signs of a growing economy, with more locally owned businesses and United States imports, such as Starbucks.

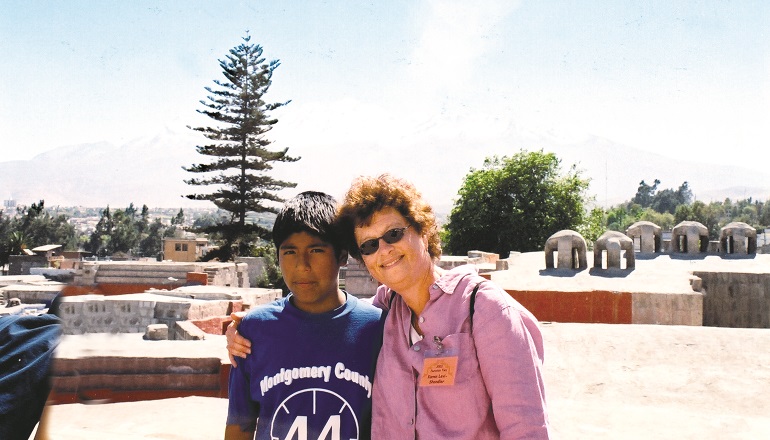

Flying to Arequipa, we drank the famous “mate de coca“a clear tea made from the leaves of the coca plant—to ward off altitude sickness. This beautiful “white city,” built entirely of volcanic stone, is known for its magnificent churches and convents. Gabriel secretly bought a crucifix to wear around his neck, a rebellious act, since we are Jewish. But we understood it as an expression of ethnic identification: It’s common for Latino youths to wear crosses.

We flew higher still, over mountains that soar into the clouds. We visited farming towns, where locals eke out a living growing potatoes and corn; the Incan ruins of Machu Picchu; and bustling Cusco, a city built on Incan stone walls. Most Peruvians have Indian ancestors, and our Indian-looking children fit in well. At home, Gabriel talks longingly about communities where people look like him. As a Caucasian in Peru, I felt what it’s like to be a minority.

Back in Lima, Gabriel’s foster mother visited us in our hotel. She was as warm and loving as she’d been 12 years ago, and said, tearfully, “I thought I’d never see him again.” Remarkably, my son sat close to her, as did my daughter. Usually they don’t take easily to strangers.

Like most families who adopt in Peru, we knew the name of our son’s birth mother, but she hadn’t wanted an ongoing relationship. We could have found out where she lived, but we felt that Gabriel wasn’t ready. To my knowledge, he had never even looked at her picture.

On our last day in Peru, Gabriel and I visited the hostel where we had lived during two adoption trips. He asked many questions—What did we do here? Whom were we with?—to recreate our first days together.

Since our trip, Gabriel has written about the experience in school papers, and says meeting his foster mother was the highlight. Some people think he seems more mellow. As for me, the words that ran through my mind each day in Peru are with me still: Thank you, Peru, for letting me have one of your children, to love and care for and hold in my arms.