The bubbly, Midwestern woman was just trying to be loving. She had adopted two Korean daughters and went to great lengths to honor their birth culture. Her girls took language lessons, and the family celebrated Lunar New Year. To sensitize their classmates, this woman went into her daughters school each year and gave a presentation on Korea. She pointed out the country on a map, explained its traditions, and showed the children a hanbok, a traditional Korean dress.

She told me this, and I nodded and smiled, but something about what she was doing made me uncomfortable. Like her daughters, I’m an adoptee born in Asia. I was born in Taiwan, and my brothers in Korea, and our parents are white. I thought to myself: Korean-Americans do not wear hanboks every day, and her children had never worn them either — unless their mother made them. Was this mom unwittingly promoting stereotypes of what her daughters must do and be?

The experience in America

More than 268,000 children from countries ranging from China to Guatemala have joined American families since 1991. For me, these families stand out not only because they look like mine, but also because they are eager to compensate for their children’s racial differences. Almost all parents who adopt internationally try to cultivate a connection to their child’s birth land. They throw ramen noodles into salads, remodel their homes in Asian motifs, and spend thousands of dollars to send their children to language schools and heritage camps on other continents.

My parents did some of these things. Yet I can’t help wondering if parents sometimes overdo it, idealizing cultures and families that no one in their families has ever met, ignoring the complex experience of being Asian in America.

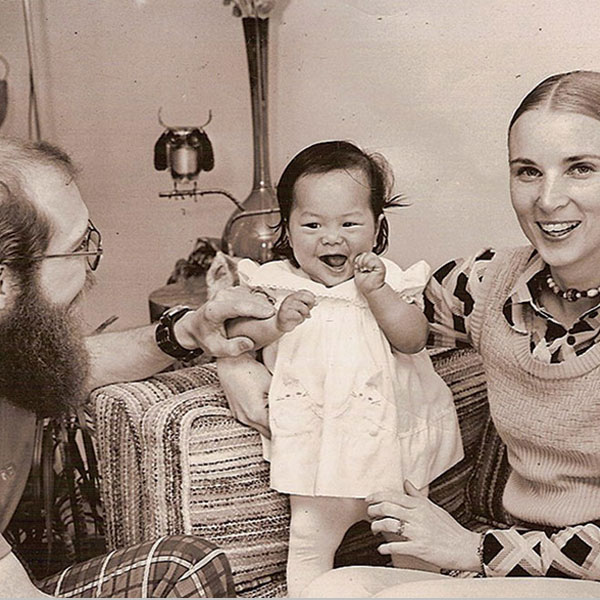

When my parents adopted me, from southern Taiwan in 1974, social workers were still telling multiracial families that they should help their children assimilate into the American culture. Focusing on differences might cause the child to feel out of place; love would conquer all. But, in the 1980s and 1990s, the adoption community began to see flaws in the love-is-color-blind philosophy. Grown adoptees — many of them Korean-born — began to talk about their self-loathing, racial taunting, and the loss of their birth cultures. Such talk sent the pendulum swinging the other way. Adoption advocates, from social workers to the ministries of foreign governments, now consider preserving heritage to be vital.

Eager to do the right thing, many adoptive parents — mostly white and middle to upper-middle class — have tried to compensate for their children’s loss of culture. Sociologist Heather Jacobson, author of Culture Keeping: White Mothers, International Adoption, and the Negotiation of Family Difference, says that mothers with children from China told her they felt a deep connection with the country of China, its traditions and people. Yet she also said that these feelings do not translate into actual friendships or deep, meaningful day-to-day relationships with Chinese people here in the United States. Many moms arranged contact with immigrant Chinese, rather than third-generation Chinese-Americans, because recent immigrants were genuinely Chinese. Fan dances, tea ceremonies, and holidays are more accessible and more alluring than the actual, complicated experience of being Asian-American. But the museum view of culture ignores the realities of life as a racial minority in America.

I’m glad that my parents took us to ethnic festivals and restaurants, but more significant was my meeting Asian-American role models: journalists, mothers, friends. So often families are more comfortable talking about culture because it’s something we can celebrate, and food, music, and other fun things are associated with culture, says Amanda Baden, who was adopted from Hong Kong, and is now a psychologist who advises adoptive families. Being open to race is just as important, she says.

It wasn’t until I met my birth family, at age 23, that I started trying to be Chinese. My new family members were not poor, farming people. They were a mix of traditional Chinese values and modern influences. Taiwan also challenged my assumptions, with its Buddhist temples sitting next to spanking-new skyscrapers. After spending years ignoring my heritage, I started to study Mandarin, and I took a year off from work to immerse myself in Chinese language, culture, and history.

But my enthusiasm took me only so far. Today I can make small talk with the Chinese owner of a grocery store, but I can barely have a one-on-one conversation with my birth parents. I enjoy visiting my family in Taiwan (and I adore my birth siblings), but I will never fit perfectly into the country where I was born — and I’m OK with that.

As authentic as any

It is tough to maneuver the dynamics inside and outside the confines of a multiracial family, but there is a middle ground. My parents celebrated my heritage and that of my brothers. They incorporated Asian-American adults into our social circles. They were always open to discussions of race, and ultimately they let my brothers and me decide how our past would influence our present.

Today, my life reflects many places and influences, including, but not exclusive to, where I’m from (Taiwan), where I grew up (Michigan), and where I live (Argentina). Most adoptees ultimately come to their own view of culture and adoption, and most multiracial families have a wide, global view of themselves. Our backgrounds, beliefs, and practices — however complicated and dissonant they seem — are authentic. We are the immigrant story, and our culture is as rich as the one we left behind.

This is an adaptation of an essay originally published in the Boston Globe Ideas section. Reprinted with permission.