Twelve years passed between the moment I announced that I intended to adopt and the day I submitted my adoption application. About eight of those years were spent in pursuit of a doctorate, then searching for a job.

But for another chunk of that time — at least a year — I was pursuing the possibility that I might adopt an Arab child, which, as a Lebanese American, I thought would be ideal.

Adoption (except among family members) is so rare in the Arab world that my chances of adopting an Arab child were extremely slim. I finally realized that if I wanted to be a mother, I’d better expand my horizons. I did this by making comparisons between countries where children were available for adoption and my own cultural heritage.

I settled on adopting a Hispanic child, specifically one from Guatemala. My reasoning went like this: the links between Arab culture and Spanish culture are deep. Guatemala is at least a partly Spanish culture, and the Arabs were in Spain for 800 years.

I was still thinking about this when I learned my baby’s original last name — Hernandez — and remembered that Spanish names that ended in “ez” were the names of the Moors, the Arab Spaniards. Moreover, I knew that Lebanese have been settling in South and Central America for 100 years.

The “Spanish solution” worked for me for other reasons. I had recently spent a year and a half teaching English as a second language to women from the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. I admired their courage and felt an affinity with them that I assumed would help my future child embrace his own culture.

Once my baby arrived, all these ideas about cultural links and affinities seemed nothing more than rationales. They soon evaporated, though I was grateful that they had gotten me to the point of adopting Emilio.

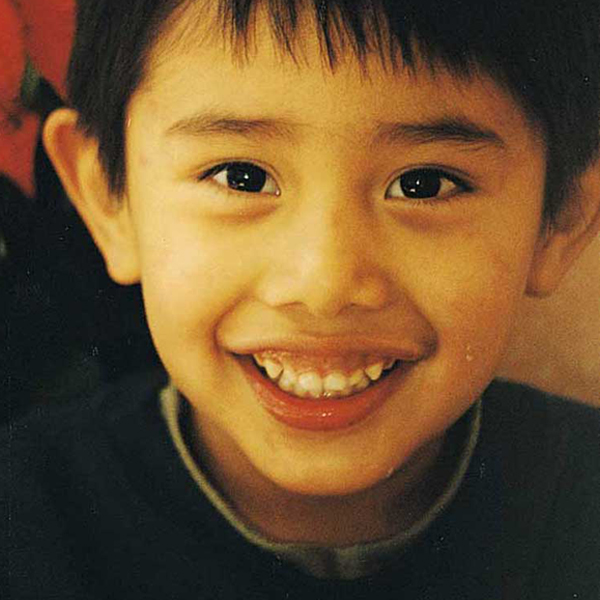

I decided that in every way Emilio was far superior to whatever my own genes could have produced. Even my mother (who had originally resisted the idea of adoption entirely) agreed wholeheartedly. (Much to our chagrin, she said, “He’s much better than any of you kids ever were!”)

He was sunshine, and I was pensive; he was outgoing, and I was shy and aloof; he was attentive and observant, and I was in my own cloud. In my 30th college reunion book I described him as my role model.

Growing Up Bilingual

What I cared most about was that Emilio grow up bilingual. I wanted him to learn Spanish, not only because that’s the language of his country of birth, but also because it’s the second language of New York City, where we live.

I hired Spanish-speaking babysitters, and, spoke to him in my own limited Spanish. A few years ago I applied for the dual language program in his new public school because he was of Spanish origin, but also because I believe the research about the positive educational impact of early language learning.

When he was rejected from that program, I was devastated. My grand plan of raising a bilingual child was being thwarted. Then, oddly, I let the matter rest. I decided that kindergarten itself was enough of an adjustment, that the added complication of being taught in two languages should perhaps be postponed.

But also at work was the suspicion that the Spanish bilingual/bicultural piece was my agenda, and not my child’s. While I have always believed in bi-culturalism, Emilio himself seems indifferent to his Spanish roots and cultural heritage right now. After three years of listening to (and apparently responding to) the Spanish of his babysitters, he seems to have retained only the word “zapatos.”

In fact, he seems more interested in his Arabic roots. When I teach him a new Arabic word, he pronounces it like a native and doesn’t forget it. (His favorites are “mazboot” which means “Right! or “Exactly!” and “habibi” which means “my friend” or “my sweetie,” and he weaves Arabic words into his conversation with an abandon that I could never muster at his age. His response to Arabic music (heard on tapes and at our eastern rite Masses) has been positive, despite — or perhaps because of — the fact that it has a totally different tonal quality from western music. (Interestingly, once during the Jewish high holidays, when the radio was playing Jewish liturgical music during an interlude between news stories, he said, “Ma, that’s like church.”)

Ethnicity maven that I am, I have made big plans where culture is concerned. But I learn (and forget) every day that Emilio has his own view of the world. Our lives are still unfolding, and what I report for each of us today is certainly different from what I will report in two years.

Now I feel what I must do is give him food for the senses from both cultures — taste the flavors, smell the spices, hear the music, and see the people of both his cultures. If I can provide these experiences for Emilio, I think I will have done my duty to the Guatemalan in him and satisfied myself.