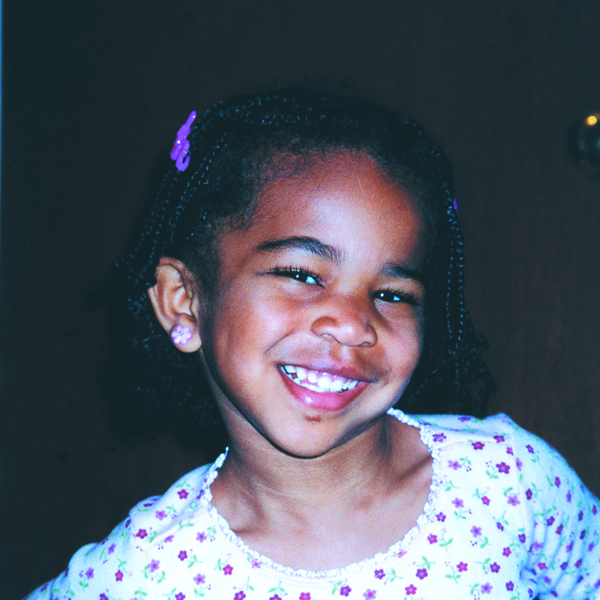

Ever since our daughter Mattéa’s hair reached what we called her “Lyle Lovett stage” — marginal hair on the back and sides, and a feathery brush on top — I’ve taken on the job of subduing, adorning, sculpting, and generally relating to it. Fixing my daughter’s hair is not, I confess, something that I have dreamed of since childhood. My scalp still twitches from the memory of my mother attempting to brush out the rats’ nests in my long, fine hair. When we were filling out the application for adoption, I was stumped by the questionnaire for white parents planning to adopt black children, which asked if I could affirm this statement: “I enjoy the many ways that I can style my daughter’s hair.” In my heart of hearts, I was hoping for a girl with silky curls that bounced around her face as she ran. What we got is a little girl who likes her hair done in lots of braids, so they “wiggle” when she shakes her head. Such a blessing.

I’m proud to say that now I truly can affirm my pleasure in the many ways I can style my daughter’s hair: in parts combed into complex geometric patterns, in braids that bounce as she runs, in two puffy pig-tails that look like Minnie Mouse’s ears. I can make a crown of braids around her head and hold it in place with butterfly clips — a style we’ve dubbed “Afro-Swedish.” I didn’t take on doing Téa’s hair as a creative outlet. I simply realized that hair is a marker of racial acceptability. I feel conspicuous as the white mom of an African-American child. I feel even more conspicuous as one of two white moms of that black child. My family doesn’t look the way families are “supposed to” look. I’ve lived as a lesbian long enough to tell myself pretty easily that if people don’t like it, they can lump it. If white people look down on my having a black child, too bad. But if black people disapprove of our unorthodox family, the place inside that longs for acceptance — not only for myself, but also for my daughter — shrivels and cringes. And the first thing African-American women asked — after “Is that your baby?” — was whether we knew how to do her hair.

Thank God for people like the lady on the train, who gave us unsolicited advice on hair products one day when Téa’s hair was in newly washed chaos. In moments of embarrassment, I try to remember that these gifts are about more than hair. They represent a few bricks removed from the wall of racism that divides our country. Black people have always had to pay attention to how white people lived. It’s a basic law of survival that the oppressed need to understand the world of the oppressor. Now it’s my turn to be quiet and listen, to receive such gifts with humility and grace.

Perhaps it’s my own mix of determination and anxiety that is the root of Mattéa’s obsession with hair. “Dolly got long hair.” “That girl got long hair.” “You got pitty hair, MamaLynn.” The girl knows hair. At two, of course, she also has firm opinions about how her hair should be done. “I want ballerina hair.” What foolish mom made the mistake of pointing out to a dance-crazed two-year-old that ballerinas wear their hair smoothed back in a bun? The process is not unlike trying to smooth a lion’s mane back into a tidy chignon — if only the lion were determined that the process should work. And it does work, at least to Téa’s satisfaction, by liberal application of hair clips. But what do I tell her when she looks at the one African-American girl on “Barney” and says “I want it like her”? The one black girl on “Barney” has long, shiny, straight hair that goes into a braid down her back. “She’s a big girl,” I say, “so her hair is longer than yours. We can’t do it like that right now.” However, what I want to say is: “So, Barney, you big politically correct faker, why does the black girl have to have ‘good’ (i.e., European) hair? Why can’t our differences be genuinely different? Would it be such a terrible thing for the black girl (if there’s going to be only one) to have dreadlocks or cornrows or any of the elaborate partings and twinings and ornamentation that I see on girls at the mall?”

My daughter already knows that she’s a different color than her moms. “I’m brown!” she tells me. (OK, sometimes she says, “I’m orange!” We’re still working on colors.) At this point the fact has no more emotional weight than her knowledge that the cat is a different color than the dog (who really is orange). But it won’t be long before the world — ”Barney” producers and all — starts to tell her that straight hair and light skin and families with a mommy and a daddy are, if not better, at least “normal.” I grieve the coming of that day. But we are doing our best to prepare for it, in the limited ways in which one can prepare a two-year-old for things as abstract and mystifying as racism and homophobia. We’ve chosen to move to the most racially diverse areas of the country. (Of course, good weather and proximity to her grandparents didn’t hurt in that decision.) We try to make sure that her books and toys and videos reflect some of the diversity of her world. We give her love and hugs and kisses and chances to try new things and fail and try again. At some point all we will be able do is rely on her naturally sunny personality and profound self-confidence to carry her through. That and trying to make sure that she never has reason to lose her toddler-certain knowledge that her black, bushy, multi-textured hair is, indeed, “pitty.”