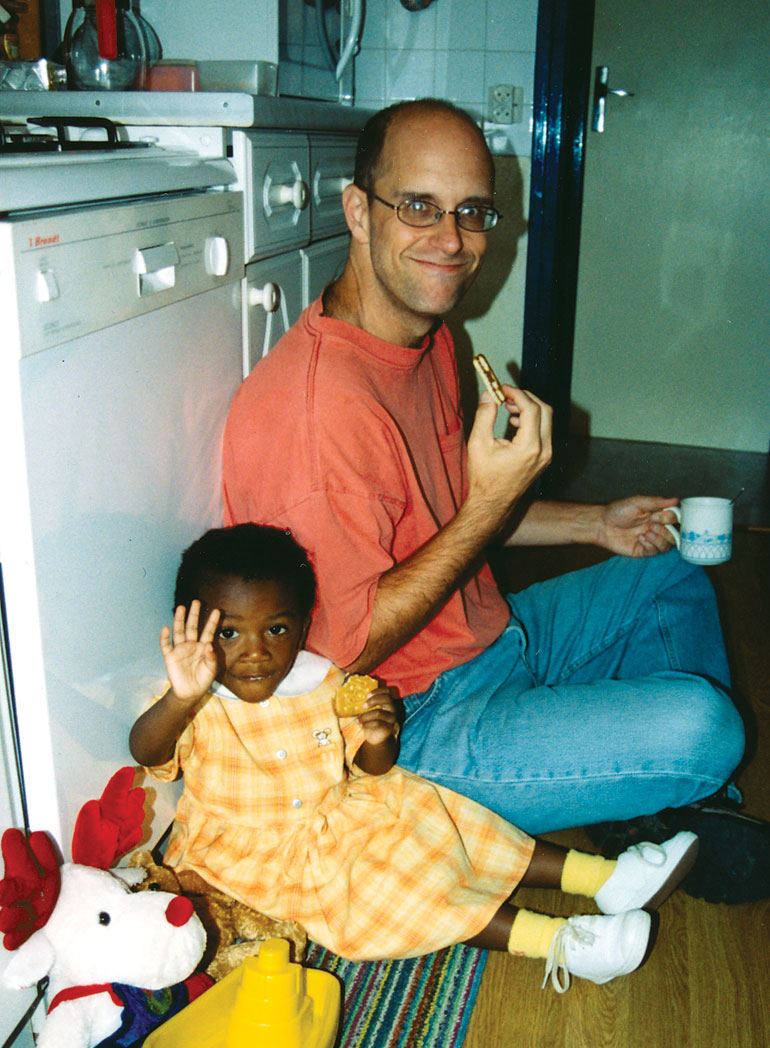

I have never stood out in a crowd. In fact, I have been known to introduce myself four times to the same person because I don’t expect anyone to remember me. That changed with the arrival of my daughter, Noelle.

My wife and I are white; Noelle is black. And even though my wife, Danielle, and I talked a great deal about race before we decided on a transracial adoption, we didn’t fully appreciate how visible our family would become. Quite simply, we now stick out in a crowd.

As we walk along the street, a neighbor calls a greeting from her car. “I saw you from over there,” she says, pointing to a distant spot. It would have been impossible for her to make out our features, but the contrast of color was enough to distinguish us.

We’re also remembered almost everywhere we go. When we run errands, the cashiers comment on how big Noelle’s getting. And when I go out alone, I’m asked by virtual strangers, “How’s that baby girl doing?” My daughter has lodged me in people’s memories.

Adoption ambassadors

Because our status as an adoptive family is so obvious, we sometimes find ourselves being questioned about the process. People ask how much it cost, what we know about the birth parents, even why we couldn’t have children of our own.

Sometimes I wonder how they would react if I said, “I see you have a child there. Where did you conceive? How much were the hospital bills? Aren’t you worried that the child will have all your genetic flaws and none of your virtues?”

At times, we take the time to educate and to clarify misconceptions about adoption. Sometimes, however, we simply want to do our shopping or eat our dinner.

We also find ourselves receiving a great deal of unsolicited advice. One African-American woman tells Danielle, “You’ll have to go get yourself some black friends. They’ll help you with her hair.” We find this comment intriguing, both for its assumption that we have no black friends and for its belief that we can simply “go get” some.

We evoke a spectrum of reactions just by stepping outside our door. There are the double-takes and stares. There are the occasional negative encounters, such as the one with the man who literally turned his back to us as we passed.

There also are the gratifyingly large number of positive reactions, such as the time the waitress grabbed Danielle’s arm and said, “I think it’s great what you’re doing!” (Danielle was momentarily confused. After all, it was just an order of tea.) In the eyes of some, Noelle has transformed us from nondescript thirty-somethings into “good” or “wonderful” people, and, in one case, “saints.”

Although I like the sound of “St. Joe,” most rewarding of all are the casual interactions with people, particularly African-Americans, who make conversation in a way that I suspect many wouldn’t if Noelle were white.

One evening, we enter a bookstore, and the white, female clerk stares at us. It isn’t the usual double-take; it is an intensely upset look. We greet her, but she doesn’t respond. A few minutes later, she approaches.

“Are you baby-sitting?”

“No.”

“She’s yours?”

“Yes. We adopted her when she was 10 days old.” The clerk’s face tightens, and we fear an unpleasant comment, but she walks away.

In a moment, she returns.

“I don’t usually tell people this, but years ago, I placed a child for adoption…. The father was black.” She looks like she is going to cry. “I’m so glad to see a family like yours.”