When my daughter Michalene was two, her favorite book was Shades of Black, with its beautiful photos of African-American children. Some kids were light-skinned, some dark-skinned, some a shade in between, and they all proclaimed, “I am Black, I am Unique! I come from ancient Kings and Queens!” Mikey liked that part. When she wanted to read the book, she would yell, “I black, I new-nique!”

When my son Danny was two years old, his favorite book was also Shades of Black. He would join in the refrain, shouting, “I black, I new-nique.” It was cute, but problematic, since Danny is not, in fact, black. I thought about altering the words to make them more appropriate for Danny – “I am white, I am ubiquitous! I come from Irish peasant stock!” It didn’t have the same ring as that kings-and-queens line.

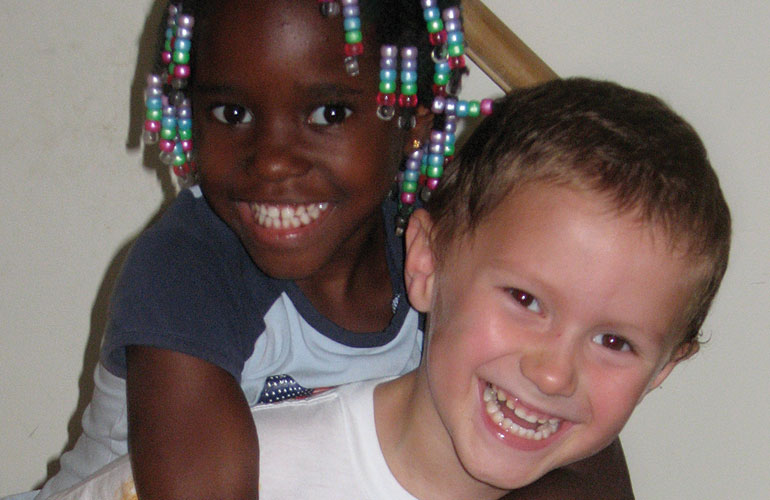

Twins, Though Not By Design

Mikey and Danny are “artificial twins” – siblings who are close in age but have no biological relationship. Mikey, who joined our family through adoption as a 19-day-old infant, was 26 days old when I realized I was pregnant; eight months and 20 days old when Danny was born. Our pre-adoption classes had focused exclusively on fostering a healthy racial identity for our African-American child. How would parenting Mikey and Danny side by side affect our perspective?

I first noticed the little things. If we were playing Chutes and Ladders, I would encourage Mikey to pick the African-American girl game piece. It would, I hoped, subtly remind her that she was not alone. She would learn that all people could participate equally in climbing ladders and sliding down chutes – or something like that. Danny would often pick the African-American boy game piece. Great! He was becoming aware that there were lots of different people to whom he could relate. He was recognizing that all people could participate equally in climbing…

Wait a minute. If it was no big deal for Danny to choose a player of a different race, should it be a big deal if Mikey did the same? I told myself, this is a minor thing, relax. The same was true with baby dolls. Like many transracial moms, I obsess about finding African-American dolls for Mikey. When she was three, she received a doll that looked just like her. She promptly named it “Baby Mikey,” after her favorite person.

Around the same time, I got a doll for Danny. I chose one that looked like he did as a baby – chubby, white, and bald. We named it “George.” Even now, at ages six and five-and-a-half, Mikey and Danny love “playing house.” While Danny is a great Daddy, George is long gone, and it is usually Baby Mikey who gets his attention. I have always thought this was great, too. After all, one of my mantras is, “Families don’t have to match.”

So, if it’s a positive thing for Danny to play with a non-white doll, why should I freak out if Mikey plays with a non-black doll? Even imaginary families don’t have to match!

Seeing Mikey and Danny together has helped me let go of those little things. But there are bigger things at play. We wouldn’t take classes, read books, and join support groups if issues of racial identity and self-worth didn’t matter to us. Mikey and Danny have taught me a thing or two about the big things, too.

All Kids Deserve Our Attention

It started, of course, with Mikey. And it started with hair. Around age three, she became frustrated because her ponytails didn’t “swing” like Mommy’s. She became firmly anti-afro and afro-puff. She also started noticing that she was darker than everyone else in her family. “I’m the only one who’s dark brown,” she would sigh. In spite of my efforts to sway her toward Princess Tiana, she was fixed on Sleeping Beauty as the paragon of loveliness.

Knowing how important it was to Mikey to belong, I stuck with her. Over and over, I listened to her concerns, affirmed her feelings, and reminded her of friends and relatives who were also of African heritage. Together we read books about hair, marveling at the intricate styles we saw. I mastered her favorite hairstyle, and she would swing her “clicky-clacky beads” contentedly. Slowly, she developed self-confidence. After starting school in our diverse neighborhood, her isolation diminished, partly due to the arrival of baby sister Mia, in 2010. Though not biologically related, the girls resemble each other, and Mikey latched on to their similarities to bolster her own racial identity.

But what of Danny – a white boy living with his biological, white parents? Surely Danny wouldn’t have any identity issues, right? Wrong. For Danny, it also started with hair. He asked me to put leave-in conditioner and sheen spray in his wispy brown locks. I humored him, though the results were tragic. Another day, I had to scrub him off after he colored himself with a brown marker. Danny, whose siblings are all of African descent, who lives in a multicultural neighborhood, started asking, “Why am I the only one who’s pink?”

At first I glossed over it with a quick, “Never mind, Danny, you know you’re cute.” Eventually, I realized that he deserved the same kind of affirmation that I heaped on Mikey. Danny needed to know that he was perfect the way he was. He deserved to have fun with his hair, knowing, as he did, that I was willing to spend hours working on Mikey’s hair. For a week he sported an edgy faux-hawk, but quickly realized “having his hair done” wasn’t as much fun as he expected. Like his hairstyle, Danny’s identity crisis was comparatively short-lived, but that doesn’t make his feelings less real.

Danny showed me that any child in multiracial families or environment might well question his racial identity. And all parents, biological or adoptive, should remember to tell their kids, “You are perfect the way you are.” Such issues are magnified in a transracial adoption, but they are not limited to transracial adoptees. Somehow, that is comforting to me. Black or white or other, we all need to be reminded that we are unique.