I remember fifth grade. It was a time of transformation — the year I left behind a life in which every day was the only day, and consciously turned my thoughts to the future. My memories of the years before consist of isolated tableaux, like exhibits in a wax museum. Memories of the years since roll by at high speed: college, graduate school, marriage, jobs, apartments, the birth of my youngest child.

And what of the birth of my eldest son, a fifth grader himself now? That I don’t remember. He was born thousands of miles away, in Korea, a land I’ve not yet seen. It is a place which figures in the foods our family eats, the folktales we read, the page marked in our atlas — but not in our memories. Whatever his life would have been like had he stayed, today he’s squeezed with his classmates into what was once his school’s cafeteria. Temporary walls divide the space into three tiny classrooms crammed with maps, hamsters, backpacks and blackboards. It is an indication of the times, but not of the quality of his education. I claim the room has no windows, he insists it does. For him that classroom opens up in all directions. He doesn’t really need windows to see the skies of the future: he is in fifth grade, they are the brightest blue imaginable.

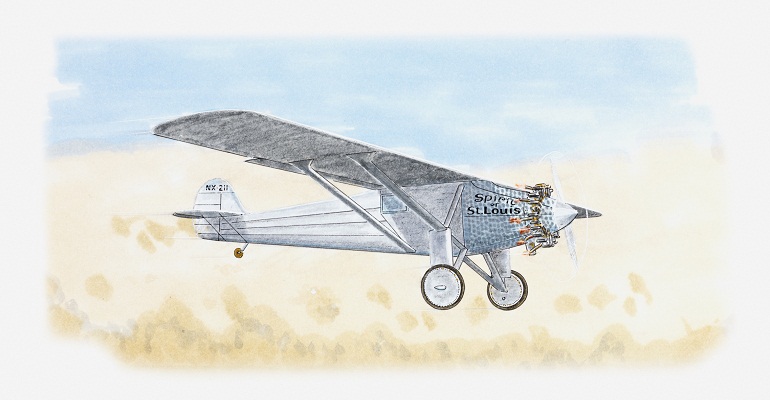

Since September he has been preparing for an annual event put on by the fifth graders in our small town. Every child selects a historical figure who has inspired them. They research and write about these people’s lives, paint scenery, put together costumes and props. When all the preparations are done, the children, dressed as their heroes, stand motionless in those crowded classrooms as picture-taking parents, siblings, and schoolmates visit this year’s “Wax Museum.” I had hoped my son would choose to portray someone Asian — maybe Ghengis Kahn? I told him it was a chance to celebrate his heritage and wear a great costume. With the clarity and extreme tolerance he inevitably brings to his dealings with me, he pointed out that Ghengis Kahn was not Korean, and not too inspiring either. Anyway, he’d already decided: he was going to be Charles Lindbergh.

So, on the big day my husband and I climb down the steps to those make-shift basement classrooms to see our son in his makeshift helmet and flight jacket. His props are few, the pilot traveled light: a pen, a chicken sandwich, an old canteen. I pick up his report. “I chose Charles Lindbergh,” he wrote, “because he was the first person to prove that people could fly across oceans. Now people fly across oceans all the time. Lindbergh is special to me because I also flew across an ocean when I was very young.” My son has proved me wrong. Well meaning and concerned, but wrong. He sees clearly what his heritage is, and will not limit it as I would have done (or perhaps as Lindbergh himself might have, given his isolationist sentiments during World War II). I smile. My son maintains his steady gaze, the same one Lindbergh wears in those grainy post-flight photographs: two proud young men ready to change the world.

I look around the room. Standing in front of their painted backdrops are queens and kings, athletes and astronauts. Patriots from Eisenhower to Rosa Parks, and pop icons from Cleopatra to Marilyn. A child who can see and hear is Helen Keller, a boy with the build of a star linebacker is the Olympic gymnast Kurt Thomas. One girl, newly arrived from Puerto Rico, holds the flag of another immigrant, the Revolutionary war figure Eliza Pinckney. A Caucasian Jimi Hendrix cradles his guitar; a Caucasian George Washington Carver holds a shovel and a handful of dirt. All the children heed their teachers’ admonitions to “keep still.” But only for the moment: in their immobile faces eyes burn as no wax figure’s ever will. I look at them and think to urge them to hurry, to burn their wax selves at both ends; life is short, and it is beautiful. And yet, I look at them and want to warn them not to fly too close to the sun. They need neither piece of advice; having chosen their heroes well they are inspired.

When this day is done they will put aside their costumes, pick up their books, and begin again the task of becoming heroes themselves. Martin Luther King said, “I have a dream…children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” I see a nation where this is not always true. But, like the window in his classroom, my son and his classmates see it differently. They study the past, but down in that cafeteria they are creating a new world. Fifth grade is a time of transformation.