"What would you think if we were to adopt an African-American baby?” I asked my older brother one evening.

“I don’t think you should,” he said. “It would just be too hard to raise a child of another race.” Deborah and I raised a conspiratorial eyebrow at one another. My brother didn’t know that we were already in the process of adopting an African-American child, a girl who was to be born in less than a month.

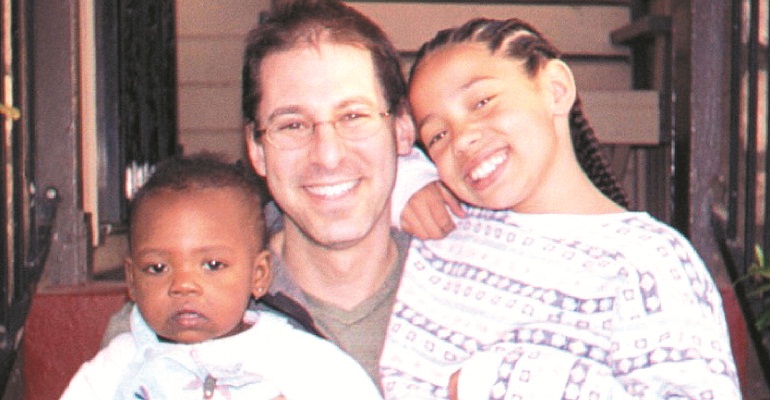

Fast-forward two and a half years. My brother—aka “Crazy Uncle Joel”—is swinging twirling my daughter, Nava Abigail, in joyful abandon. Occasionally I tease him about his initial concerns, but I can’t say that he was alone.

Embittered, exhausted, and emotionally shattered by our years of fruitless infertility treatment, Deborah and I had begun to discuss adoption with growing commitment. Besides our desire to be parents, it seemed right for other reasons. As a rabbi serving the Jewish community, it felt increasingly difficult to function as a spiritual leader when I couldn’t share the experience of raising children, an obligation our tradition holds dear.

Knowing of the need for families for minority children, we registered with the county’s Fost/Adopt program, which places foster children who are likely to be available for adoption. But we worried about the challenges of transracial adoption and religion. Could white, Jewish parents prepare a black child for living in a race-conscious and sometimes racist society?

We were also worried about bringing up an African-American child as a religious Jew—a member of a minority race within a minority religious community. There are few Jews of color in the United States, and they stand out in Jewish communities of European descent. Worse still, she would be a rabbi’s daughter! Oy vey!

Taking the Leap

But when we heard from an adoption attorney we knew, we weren’t about to walk away. She told us of an African-American woman, eight months pregnant and anxious to find an adoptive family. Another couple had dropped out at the last minute—due to their growing hesitation about transracial adoption.

As soon as we met Denna, our concerns about race began to recede. She was a bright, beautiful, and vivacious woman. She laughingly cautioned that she was so outgoing that we soon wouldn’t notice any difference in our skin color. And she was right. When she gave birth a month later, my wife and I were in attendance. I cut the umbilical cord, and we held our new daughter.

Now that we’ve melded into a loving family of three, my wife and I are jolted when strangers fail to recognize the tender ties that bind us. At our day care facility, the teacher of an older class could no longer contain her curiosity. “What is your relationship with this little girl?” she asked me. “She seems so attached to you!” Despite months of watching me drop off and pick up my child, this woman had been unable to assign the word “family” to our relationship. When I told her that Nava is my daughter, the woman blanched in embarrassment. Her apologies followed for weeks after.

I have become less forgiving when these incidents occur. Can’t they see that she’s our daughter? It must be obvious in the tenderness and concern we display for one another. Occasionally, as I catch a glimpse of the two of us in the mirror while I’m arranging Nava’s beautiful curls, I am momentarily startled by the contrast of our skin. I’ll ask, “Who is this little girl in my arms?” And I respond: “My daughter, of course! Isn’t it obvious?”

Race does matter. My daughter is beginning to notice differences in skin tones, and she points out black children in her books, identifying them as “like Nava.” In a largely Caucasian crowd, she focuses on African-Americans.

When Nava gets older, she’ll realize that being Jewish is another facet of her identity that sets her apart. She has already joined the community of Jews by taking part in a mikvah ceremony, a ritual bath that marks her conversion to Judaism. She is familiar with our weekly Shabbat and synagogue observances, and she joins in with me during my morning prayers. When she's older, Nava will celebrate her bat mitzvah, the affirmation of her Jewish identity.

There is probably no one more “colorblind” than a member of a transracial adoptive family. But we also want Nava to celebrate the differences that make her who she is. With the help of organizations that offer information and support, Deborah and I have been learning how to raise our daughter to be a confident African-American, Jewish woman, knowledgeable and proud of her cultural history and heritage. We maintain close contact with Nava’s birth mother, who is an extraordinary role model. We live in an area where Nava will see families that look like ours.

My daughter will face many difficulties in her life. But my wife and I, along with our extended family, are doing what we can to ensure that growing up as an adopted, Jewish child of color will not be the most daunting.

JOIN You are viewing this exclusive AF content as a guest. To access our full Adoption Parenting Library — plus digital issues, eBooks, expert audio and more — join Adoptive Families today.  |