Phil Bertelsen, age 37, grew up in Highland Park, New Jersey, in the 1970s. An award-winning filmmaker, Bertelsen has wrote and directed Outside Looking In, a documentary examining transracial adoption in America. Growing up black with white parents, in a predominantly white suburb, Phil Bertelsen experienced transracial adoption firsthand.

He says, “On a personal level, I recognized my adoptive family as the people I love and trust most in the world. Yet growing up, many made me feel I was out of place in the back of the family station wagon.”

Having no contact with a black community left him with burning questions about his place in the world outside his family: “I found myself wondering which factors — physical, emotional, historical, social — determine where I belong.”

Outside Looking In traces his ongoing exploration of these issues, as well as the story of his sister, Aline, and her two sons adopted transracially a decade ago. The film also follows Walt and Ellen, a white Midwestern couple currently in the process of adopting, as they meet Diane, an African-American woman placing her son for adoption.

With these three narrative threads, the film weaves a 30-year history of transracial adoption in America. Phil talked to us recently about his life as a transracial adoptee, Outside Looking In, and what he hopes to offer people touched by transracial adoption.

AF: Tell us a little about your background. Where did you grow up? What was your family like?

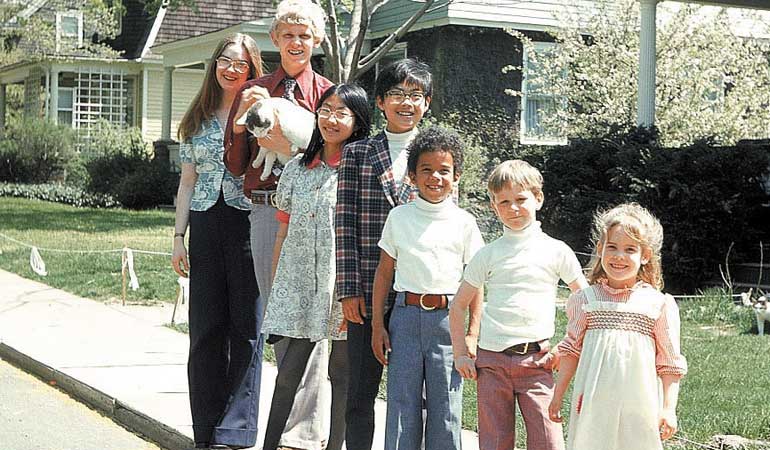

PB: I grew up in a family of seven children. While I’m not the youngest, I was the last to arrive to what was an adoptive family with two children from Korea; one Caucasian (my brother left on the stoop of a local church); myself, a biracial African-American; and three children born to my Norwegian parents. We grew up in a relatively diverse, but segregated suburb in central New Jersey. Our family was the only family of color in our part of town. We didn’t come into contact with other children of color until we attended the junior high school across town. We were raised in an environment that did not entertain conversations about three things: race, religion, and money. I’m not entirely sure why, but when those subjects happened to come up, they usually led to an uncomfortable debate. My parents were very Scandinavian in that way. They avoided confrontation at all costs.

AF: When did you first become aware of racism?

PB: My first encounter with racism occurred when I attended junior high school and came into contact with other students of color for the first time. There was a school-wide race riot, and I had to choose sides — black or white. This was not something I was accustomed to or equipped to do. In the meantime, my blonde “girlfriend” at the time told me we could no longer be together because her mother didn’t want her to be seen with “a nigger.” Until then, I didn’t know what that meant, let alone think that I might be one.

AF: Growing up, did you ever feel isolated or alone?

PB: Yes. Being the only child of color in an all-white neighborhood school made classes isolating — an isolation that, as a child, I couldn’t identify. So I tried to fit in by being a “class clown.” I felt a part of the group when I made other kids laugh. Unfortunately, my teachers weren’t so appreciative or understanding, and I was sent to the principal’s office, repeatedly, for disciplinary action.

AF: Did your family expose you in any way to other African-American adoptees or to members of the black community?

PB: No, they did not. I’m not exactly sure why; but I don’t think they felt it was important. “A child is a child is a child,” my mother would say. “They all have the same likes and dislikes.”

AF: What experience in your life helped you to connect with the African-American community? What helped you to develop a positive sense of identity?

PB: Being around students of color at college (and having a black college roommate) changed my perspective and enabled me to recognize and better appreciate who I was historically, culturally, and emotionally. For the first time in my life, I was in a peer group that I resembled and, who, unlike me, came from a black cultural experience — one built on pride and heritage, and for whom black culture was not a curiosity, but a way of life. It taught me to move beyond the questioning and learn about what I was missing.

AF: What advice would you give to prospective white adopters or white families raising black kids?

PB: The one thing I would say is “Be not afraid!” Go outside your comfort zone to embrace your child’s culture of origin. Attend services at faith institutions in communities where your child’s culture of origin is dominant. Patronize the local businesses in those neighborhoods and make acquaintances. Those allies can be useful later as they might be willing to act as mentors to your child, should that be necessary. Recognize that there will be things — culturally speaking — that you cannot give to your child. It’s good to have others in your life whom you can rely on for that. I would also suggest that you move to such neighborhoods if possible, or consider placing your child of color in a diverse school environment, if nothing else.

Do this not for your child’s sake, but for yours as well. It can be a life-enriching experience beyond your imagination, but it requires a commitment that will sometimes be uncomfortable. Ultimately, though, it will make you the truly multiracial family that you have become and give your child a fighting chance at having a positive self-image in a world that doesn’t necessarily promote it.

AF: When and why did you decide to make this documentary?

PB: I’ve been thinking about it for as long as I’ve been involved in media. But what pushed me into action was the Multiethnic Placement Act of 1994, which essentially prohibits race from being a factor in adoption. I don’t think race should be a prohibiting factor to the extent that it once was, when black children were held in foster care indefinitely while attempts were made to locate a black family.

I’m not a strict “same-race placement” advocate. But I do think that there’s a problem with a law that doesn’t allow race to be a part of the dialogue. Families should at least be probed as to what their relationship — their community’s relationship, their family’s relationship — is with a child’s culture of origin. I wanted to promote dialogue.

AF: A heated discussion has taken shape on the Outside Looking In Web site. Did you anticipate setting this in motion?

PB: The Web site’s demonstrated that people need to talk about this, and they need a forum in which to do it. The film was was an opportunity for me to have a dialogue with my family — to ask questions I hadn’t found a way to ask. I wanted to share that as a way to demonstrate that it’s okay to talk about this stuff.

AF: When did you begin to connect with African-American culture as we see you trying to help your nephew connect in the film?

PB: When I got to college, I immersed myself in a culture I hadn’t been exposed to — black culture. I asked for a black roommate, and I got someone from the Bronx, which couldn’t have been further from my suburban high school experience. It wasn’t easy going entirely, but I learned quickly that two worlds coexist: one black and one white. I was surprised by that — startled and amazed and rudely awakened. From that point on, I made a concerted effort to find out what I’d been missing.

AF: How did you come to seek out the foster family who raised you from age 16 months to four-and-a-half years, which we see played out in this film?

PB: By four-and-a-half, when I was adopted, a child’s formed a certain identity — and I was wondering who that person was who got me there. So I went and found her with the help of social workers who have long been aware of my many inquiries. It boggles my mind that I can’t remember much of my life with them — four years. I think it has something to do with being that age and being removed from what’s familiar. You kind of shut the door in an effort to feel permanent somewhere.

AF: At one point your mother says that she and your father didn’t have access to all the support groups and information sources that adoptive parents have access to today.

PB: “—and whatever your gut told you, you did.” That’s my mom! If I can say I have an ounce of that kind of steely resolve and determination to trust my instincts, I’m having a good day.

AF: How do you think things might have been different if your family had had access to all of those resources?

PB: I think we would have lived a little differently. I’m not sure we would have changed towns, but we probably would have lived in a different part of town. We might have gone to a different church. It’s not like my parents were oblivious to these kinds of things — I think the conversation was in the wind — but it wasn’t central, and it didn’t have any real credibility because there was no empirical data or experience leading up to it. It was all just theory. We were kind of making our own map.

AF: How do you see this film fitting into the larger picture of your generation speaking out about your experiences of transracial adoption?

PB: I hope that it can be used as a tool, by agencies and organizations, lawyers and adoption workers, who want to prepare parents for what it is they’re getting themselves into. It’s pleasure and pain. It’s talking and silence. It’s a mix of all these things, and to think that it’s going to be one without the other is just misrepresenting the experience. I hope the film demonstrates that.